Nadine Strossen’s book on free speech arrives at precisely the right time

Reviewed by Carolyn Schurr Levin

These are perilous times for free speech on college campuses. So many invited speakers are being “uninvited” because of their disfavored views that the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) maintains a database of “Disinvitation Attempts.” Students have faced expulsion and faculty members have faced punishment, including dismissal, for talks, online posts, or otherwise expressing disfavored views. College newspapers have been forced to apologize for stories or advertisements labeled as offensive “hate speech.” Some have experienced the theft of newspapers from their racks. And college media advisers are increasingly fearful for their own jobs and the very existence of their media outlets due to their publication of content that might be perceived as unpopular or unwelcome.

These are perilous times for free speech on college campuses. So many invited speakers are being “uninvited” because of their disfavored views that the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) maintains a database of “Disinvitation Attempts.” Students have faced expulsion and faculty members have faced punishment, including dismissal, for talks, online posts, or otherwise expressing disfavored views. College newspapers have been forced to apologize for stories or advertisements labeled as offensive “hate speech.” Some have experienced the theft of newspapers from their racks. And college media advisers are increasingly fearful for their own jobs and the very existence of their media outlets due to their publication of content that might be perceived as unpopular or unwelcome.

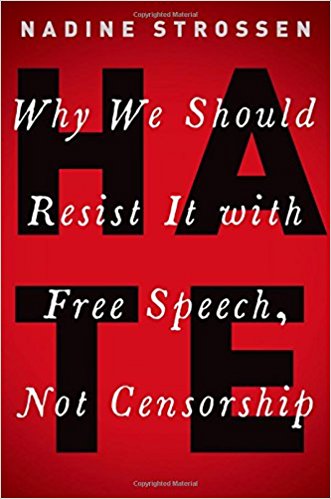

Enter Nadine Strossen at precisely the right time with her consequential new book, Hate: Why We should Resist It With Free Speech, Not Censorship. Strossen, a professor of constitutional law at New York Law School and a former president of the American Civil Liberties Union, provides needed elucidation about the grossly misunderstood concept of “hate speech,” not just on college campuses, but in our larger society. Strossen dispels the notion that “hate speech” is not free speech and she vehemently argues that the remedy for speech that might seem harmful to some eyes is more, not less, speech.

The legal issues are quite complex. Strossen breaks them down and explains them without the legalese of many First Amendment primers. She begins by offering an index of “Key Terms and Concepts,” defining “hate speech,” “hate speech” law, “counterspeech” and other key terms as a complement to the analysis that follows. “Hate speech,” in our popular discourse, she explains, “has been used loosely to demonize” – and suppress – “a wide array of disfavored views.” Because it has no single definition, she puts it in quotation marks throughout her book. She defines “hate speech” laws as any regulations by a government body of constitutionally protected hate speech, including “speech codes” implemented by public universities. These, she argues later in the book, are not the answer.

Strossen uses a situation at Harvard University to illustrate the inherent problem of defining “hate speech.” Some students hung Confederate flags from their dormitory windows, which prompted other students to protest by hanging swastikas from their dormitory windows. The students who displayed the swastika were not trying to convey hateful ideas, but rather they were condemning the racism that the Confederate flag connoted to them by equating it with the swastika. Should the swastika displays count as “hate speech,” Strossen asks, or as anti-“hate speech”? Then other students publicly burned a Confederate flag, a symbol to many Americans of their Southern heritage and a tribute to their ancestors who were killed in the Civil War. Is the flag burning “hate speech” or, as the students who burned it believed, also anti-“hate speech”?

Strossen readily acknowledges that college campuses “must strive to be inclusive, to make everyone welcome, especially those who traditionally have been excluded or marginalized.” But, she argues forcefully, “that inclusivity must also extend to those who voice unpopular ideas, especially on campus, where ideas should be most freely aired, discussed and debated.” Encountering “unwelcome” ideas “is essential for honing our abilities to analyze, criticize, and refute them.”

But doesn’t “hate speech” have negative impacts, including emotional pain? Surely it does, Strossen says. But allowing the government to silence ideas that are disfavored, disturbing, or feared creates even greater problems. Of course, this does not mean that the government cannot take action against what has been labeled “true threats,” “bias crimes,” or “harassment.” Violent, discriminatory or criminal conduct, such as assaults or vandalism, is not protected and should be punished. Discriminatory or hateful ideas, though, should not be punished, but rather should be rebutted, according to Strossen.

Strossen’s foray into “hate speech” is far broader than academia. Among other things, she looks at private companies that have attempted to enforce “hate speech” bans with difficulties. The enforcement of bans on “hate speech” by social media platforms, for example, is vague, subjective and inconsistent, Strossen says.

Yet, most relevant for college media advisers is Strossen’s argument that college and university campuses are venues where free speech and intellectual freedom should be most secure, where “hate speech” should be remedied with counterspeech, not with the shutdown of speech. When many public universities introduced “hate speech” codes in the late 1980s, they were successfully challenged in courts as being vague and overbroad in violation of the First Amendment. In fact, Strossen said during a recent telephone interview about her book, “every single speech code that has been challenged has been struck down.”

But it’s not only official suppression that is problematic on college campuses. Many universities are increasingly experiencing self-censorship among students and faculty about sensitive, controversial topics. This, in Strossen’s opinion, is the exact opposite of what should be taking place. These topics, she writes, “call for candid, vigorous debate and discussion,” and not for suppression. She extends her argument not just to public universities, but also to private universities and online intermediaries because of “the enormous power” they wield “to facilitate or stifle the free exchange of ideas and information.” They also “should permit all expression that the First Amendment shields from government censorship.”

If the very definition of “hate speech” is so ambiguous and confusing, what is the solution to countering its potentially harmful effects? Strossen’s message is very affirmative. The best way to reduce hate, discrimination, and stereotypes is through more speech, not the stifling of speech. “Counterspeech,” which encompasses any speech that counters a message with which one disagrees, can be effective in checking the potentially harmful effects of “hate speech.” Strossen describes promising online counterspeech initiatives and studies, including tools developed by Google, YouTube and Facebook. She also describes as “remarkable” the rising resistance to hateful words by “alt-right” and similar groups. This “counterspeech chorus” emphasizes the essential role the First Amendment plays in promoting equality, inclusivity, and intergroup harmony.

In this climate, Strossen says, student journalists should be encouraged to think about the impact of their “speech.” Despite potential pushback from faculty, administrators, politicians, alumni, fellow students, or donors, student media will benefit from providing a forum for divergent or controversial views. Student journalists should be encouraged to air all views and engage in them. They, and their advisers, are “fighting for the future of academic freedom,” Strossen boldly states. What our students need to navigate the current political and social landscape, she argues, is a solid grounding in fundamental First Amendment principles. Strossen’s book is an excellent place to start.

About the Author: Carolyn Schurr Levin, an attorney specializing in Media Law and the First Amendment, is a professor of journalism and the faculty adviser for the student newspaper at Long Island University, LIU Post. She is also a lecturer and the media law adviser for the Stony Brook University School of Journalism. She has practiced law for over 25 years, including as the Vice President and General Counsel of Newsday and the Vice President and General Counsel of Ziff Davis Media.