An Ethical Analysis of the Trump Effect on Student Media

Brittany Fleming, Ph.D.

Slippery Rock University

Mark Zeltner, Ph.D.

Slippery Rock University

Cody Nespor, B.S.

University of West Virginia

Abstract: On March 31, 2018, a Pennsylvania state representative used Twitter to confront and challenge the ethics of a student journalist, tweeting “…and then there is the “Editor in Chief” of the student blog/paper @CodyNesporSRU who pushes a lib agenda and [is] a horrible writer” to the feeds of his 5,500+ Twitter followers. Closely resembling the social media etiquette of President Donald Trump, or what we will refer to as the Trump Effect, this post caught the attention of not only the student journalist mentioned in the tweet, but student media advisers and professional journalists across the country. Unfortunately, this type of behavior is becoming more common in our society and student journalists need a framework for dealing with similar issues.

Abstract: On March 31, 2018, a Pennsylvania state representative used Twitter to confront and challenge the ethics of a student journalist, tweeting “…and then there is the “Editor in Chief” of the student blog/paper @CodyNesporSRU who pushes a lib agenda and [is] a horrible writer” to the feeds of his 5,500+ Twitter followers. Closely resembling the social media etiquette of President Donald Trump, or what we will refer to as the Trump Effect, this post caught the attention of not only the student journalist mentioned in the tweet, but student media advisers and professional journalists across the country. Unfortunately, this type of behavior is becoming more common in our society and student journalists need a framework for dealing with similar issues.

Using a modified version of the Potter Box created by Loy D. Watley (2014) as an analytical framework, this case study examines the aforementioned student journalist’s ethical action and response to the state representative’s tweet. Alternative outcomes to this specific situation will be discussed, as well as recommendations on how to handle the Trump Effect in the future, without harming the reputation of the journalist.

Introduction

Social media’s impact on democracy continues to evolve as users find new ways to communicate with each other. Twitter, for example, has become a driving force for facilitating discourse between political figureheads and their constituents. Often times, this discourse is less than productive and frequently abused by those in power. We see frequently with President Trump, for example, when he tweets at journalists, attacking and accusing them of agenda setting and producing fake news. What happens, however, when this abuse trickles into local government and starts to affect our communities and universities?

Unfortunately, this type of behavior is becoming more common in our society and student journalists need a framework for dealing with similar issues. This paper investigates the ethical considerations involving an online interaction between State Representative Aaron Bernstine and Cody Nespor, the former editor in chief for the student newspaper at Slippery Rock University. Specifically, this case study focuses on Nespor’s ethical decision-making process as it relates to his response to Bernstine’s tweet.

This analysis begins with a review of the literature as it applies to journalistic ethics and political discourse. An overview of the Potter Box is then presented, along with alternative decision-making models used for assessing the decision-making process. Finally, a five-step modified Potter Box is applied to the case at hand. At the end of the analysis, we provide recommendations that student journalists and college media advisers can use when handling similar situations in the future.

Ethical News Values

Journalists are expected to operate in the same fashion: to seek and report the truth, to minimize harm, and to act with independence, accountability and transparency (SPJ 2014). Specifically, the Society of Professional Journalists’ Code of Ethics states that journalists need to “distinguish between advocacy and news reporting,” adding that, “analysis and commentary should be labeled and not misrepresent fact or context.” In terms of acting independently, the SPJ’s Code of Ethics reiterates that journalists should “be vigilant and courageous about holding those with power accountable.” In terms of transparency, the SPJ’s Code of Ethics states that journalists should “expose unethical practices of journalists and the news media.” The Radio, Television, and Digital News Association (RTDNA) provides a broader overall perspective on how journalists should behave when newsgathering. The RTDNA states, “the right to broadcast, publish or otherwise share information does not mean it is always right to do so. However, journalism’s obligation is to pursue truth and report, not withhold it” (RTDNA 2015). These concepts all exemplify the ethical behavior of most working journalists in relation to politicians and all other public figures.

In terms of applied ethics, the field of journalism argues that justice or fairness, plus avoiding doing harm, is central to moral behavior (Raftner and Knowlton 2013). These ideas, respectively, are rooted in the two pillars of rational thought—Kant’s deontology and Mills’ utilitarianism (Knowlton and McKinley 2016). Further, Christians, et al. (1998) describe several categories of moral obligations for those in the profession of journalism: duty to oneself; duty to clients/subscribers/supporters; duty to the organization at which one is employed; duty to one’s colleagues; and duty to society. However, Stiles (2005) stresses that at the forefront of any journalistic decision is the last point, one’s duty to the public or society. Codes of ethics and mission statements outlined by professional associations such as the Society for Professional Journalists, the Radio, Television, and Digital News Association and the Online News Association are perfect illustrations of Kant’s, Mill’s, and similar ideologies. Each organization identifies their devotion to reporting fair and accurate information to the public, which encapsulates the double duty of acting in fairness and causing the least amount of harm (SPJ 2014; RTDNA 2015.; ONA n.d.).

However, a Feb. 17, 2017 statement from President Donald Trump openly challenged the ethics of the free press, when he used Twitter to exclaim, “The FAKE NEWS media (failing @nytimes, @NBCNews, @ABC, @CBS, @CNN) is not my enemy, it is the enemy of the American People!” The use of Twitter in politics to openly attack journalists is what we are calling the Trump Effect.

Journalistic and Political Discourse

It should be noted that Donald Trump is not the first president to have a contentious relationship with the press. In his 2014 article “The Complicated History between the Press and the Presidency,” Jason Daley points out that Richard Nixon banned the Washington Post from the White House during the height of Watergate. This unethical attempt to muzzle journalists ultimately backfired. Daley also indicates that although Lyndon Johnson had a seemingly warm relationship with Post editor Katherine Graham, he used that relationship to manipulate his press coverage to his advantage. According to Daley, uncomfortable press relations date back to George Washington who expressed dismay that his farewell might not be properly covered in the press.

But presidents, up until Trump, have generally refrained from publically questioning the ethics of the press. In a recently discovered document, Harry Truman privately wrote that, “When the press is friendly to an administration the opposition has been lied about and treated to the excrescence [sic] of paid prostitutes of the mind” (Massarella 2017). But Truman’s public stance toward the press, while combative, was also ultimately respectful and mutually beneficial. To be clear, an ethical relationship between the press and a politician, specifically a president, does not inherently imply the relationship is warm and personal. But in the past, it was generally understood that both the politician and journalist benefitted from a fairly respectful, working relationship.

Returning to the case at hand, from an ethical perspective Bernstine’s personal attacks on a student editor are indicative of a larger story being written every day by Donald Trump using social media, in most cases Twitter, to bypass traditional media outlets and create an often-false narrative with his target audience. According to an article by Terry Collins for C/Net, longtime Republican strategist Rick Wilson says that Trump’s “cozying up” to TV and newspaper reporters is no longer necessary (Collins 2018). He adds that now political candidates understand the political landscape has changed because of social media.

In the Bernstine incident, the most striking similarity to Trump’s social media strategy is a willingness to attack journalists, even student journalists. This should come as no surprise, however, when considering the 2015 Batchelder-Trump Twitter spat. In short, 18-year-old Lauren Batchelder experienced the Trump Effect after challenging him on Twitter, posting that she did not believe that he was a “friend to women.” After a series of mild back-and-forths, Trump tweeted one more time, calling her an “arrogant young woman” who questioned him in a “nasty fashion.” The Washington Post reported that Trump’s staff was “stunned he went after a college student” (Johnson 2016).

Interestingly, there was another recent example of a Pennsylvania state representative using social media as a means of attacking someone personally. In this case the social media was Facebook and the attacks were on an opposing politician. According to an article by Marielle Mondon by The Voice, another Pennsylvania state representative from Butler County, Daryl Metcalfe, used his Facebook account to call Democratic State Representative Chris Rabb a “liberal loser” and Democratic State Representative Brian Sims “a lying homosexual” (Mondon 2018). While this example does not involve journalists overtly, it does indicate that politicians, even on the state level, are now using social media as a way of bypassing the traditional media and airing their grievances directly to their constituents. Ironically, traditional media picks up these interactions and then covers the social media kerfuffle that result.

The ultimate result of this media strategy, when employed by politicians on social media, is an increasing lack of trust of the traditional or “mainstream” media. This undermines journalists’ role as the unofficial fourth branch of government in a democratic society. As demonstrated earlier, disputes between politicians and journalists date back to the dawn of our government and they are an essential part of a free society. Thus, journalists have always needed, and will always need, a solid foundation to work from when faced with ethical dilemmas.

The Development of The Potter Box

While professional associations such as RTDNA and SPJ provide ethical codes as references to report by, student journalists need a practical framework for applying such codes. One solution is the Bok Model (1978), which says ethical decisions can be analyzed by asking three questions: 1. How do you feel about the action?; 2. Is there another professionally acceptable way to achieve the same goal that will not raise ethical issues?; 3. How will others respond to the proposed act? (Patterson and Wilkens 2014). Similarly, the Ethics Check framework suggests a decisions can be analyzed by three questions: Is the action legal?; Is the action balanced?; How does the action make you feel? (Blanchard and Peale 1988). A third framework is the Potter Box, developed in 1965 by Professor Ralph B. Potter of Harvard University, which centers on an objective analysis of situational facts, values and principals, and constituencies of the decision-maker in an ethical dilemma (Potter 1965, 1972).

Like many other ethical decision-making models, the Bok and Blanchard-Peale models expect a decision-maker to operate on their own moral and ethical principles, allowing extreme flexibility in a variety of fields and contexts. However, while the adaptable and simple nature of these frameworks are relatively easy for a student journalist to follow, it can be argued that neither begin with an objective analysis of the dilemma prior to taking action. The Potter Box, on the other hand, forces the decision-maker to assess if the weight of moral obligations to particular constituencies warrants or justifies an action that could potentially harm other constituencies or cause negative outcomes (Watley 2014).

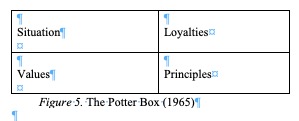

Solutions using the Potter Box (Figure 5) are defendable through four transparent quadrants: definition, values, principles, and loyalties (Christians et al. 1998). It is important to note that during the decision-making process, these dimensions should be considered a systematic cycle, rather than a linear set of isolated questions. According to Stiles (2005), the fluid structure of the four quadrants allows for the analysis of complicated situations on varying levels, such as personal, organization, institutional, and societal (Spence and Van Heekeren 2005). Using the Potter Box, an ethical dilemma can be assessed holistically and with caution before any action is made through the moral lens of the decision-maker, as well as alternative lenses and perspectives. Because of this characteristic, the Potter Box is commonly utilized in journalism and public relations. In fact, Public Relations Society of America’s (PRSA) Code of Ethics closely resembles Ralph Potter’s ideals (Smudde 2011). In six steps, decision-makers are advised to define the specific ethical issue/conflict, identify internal/external factors that may influence the decision, identify key values, identify the parties who will be affected by the decision and the decision-makers obligation to each, select ethical principles to guide the decision-making process and, last, make the decision and justify it (Fitzpatrick n.d.). It is clear that values, principles and loyalties are at the core of this code.

In addition to aiding a decision-maker in viewing a dilemma from multiple perspectives, the Potter Box can be used as a tool for determining and prioritizing competing loyalties. For example, Carveth (2011) used the Potter Box to analyze the Facebook-Google dispute of May 2011. In this case, Facebook approached the public relations firm Burson-Marseteller, with an idea to run an anti-Google campaign, which would require the firm to pitch stories to newspapers and blogs claiming that Google had been invading users’ privacy. Putting their reputation at stake, B-M agreed. The truth about the campaign surfaced when a blogger, who had been approached to run the anti-Google story, leaked a series of emails from the firm and humiliated both the firm and Facebook.

In his analysis, Carveth explains that Burson-Marseteller had three major loyalties: to the public, to their client and to themselves. In this case, B-M prioritized themselves first, by taking on a major company like Facebook for both portfolio and financial purposes. In doing so, the firm put the best interest of the public to the wayside while blindly leading Facebook into making an unethical decision. Clearly, Burson-Marseteller went against the PRSA Code of Ethics. Using the Potter Box, Carveth suggests an alternative route for B-M: to remain loyal to both the client, the public and themselves by refusing Facebook’s anti-Google proposal. Had the decision-makers utilized the Potter Box in the instance of this situation, this negative outcome could have been avoided.

According to Gemperlein (2004), j-schools have been operating under similar ethical guidelines and utilizing the Potter Box for several decades. The beauty of this instrument, as noted by Charles Marsh Jr., associate professor at University of Kansas’ William Allen White School of Journalism, is that it aids a decision-maker in generating an outcome that can be ethically justified to both themselves and others, with consideration of competing loyalties. Because of the Potter Box’s use of ethical pluralism, the decision-maker may apply several ethical philosophies to create a series of possible outcomes to any given dilemma with the goal of assessing the impact it may have on each loyalty (Bowen 2004). For example, Stiles (2005) applies the Potter Box to newspapers’ decisions to run sex ads for strip clubs or “gentlemen’s clubs” and services. Stiles explains that these types of ads are financially attractive to newspapers, as they can run anywhere from 50 percent – 400 percent over standard advertising rates; however, in many cases, these types of advertisements are cover ups for prostitution rings. This puts the editorial decision-maker in an ethical dilemma: use the ads as financial gain, potentially supporting and exposing readers to illegal activity? Or lose the client’s business to a competing newspaper? Stiles uses Christians, et al. (1998) to defend the idea that the media’s primary duty is to the public. As clearly outlined in this situation, like many ethical dilemmas, the decision-maker(s) at hand would be dealing with several competing loyalties: advertisers, subscribers and society as a whole, the newspaper’s reputation, and the potential financial loss or gain. After conducting a series of interviews with decision-makers at four Philadelphia-based newspapers, the Philadelphia Inquirer, the Daily News, the Citypaper and the Philadelphia Weekly, and considering the four quadrants of the Potter Box through the ideologies of both Kant and Mill, Stiles concludes that the overall decision to run sex ads is unethical due the potential of causing more harm than good to all loyalties involved. However, and as determined by the number of sex advertisements run in newspapers, ethics often take a back seat when dealing with a target audience that is more forgiving of less-ethical content.

Method of Analysis: The Modified Potter Box

As outlined in the examples above, the Potter Box can be a useful mechanism for dealing with ethical dilemmas. However, in a critique of the original Potter Box model, Watley (2014) notes three major disparities that mirror the issues above. The first issue is that stakeholders should be considered, rather than loyalties. According to business research, the term ‘loyalty’ is often viewed as a reciprocal relationship (Freeman 2009). Transitioning the terminology to ‘stakeholder’ broadens “a decision-maker’s perspective to include affected stakeholders who are not ‘loyal’ in that they have not initiated a commitment to the organization or decision-maker.” (Watley 2014). This mindset expands a decision-makers list of stakeholders to include society at large, even though they may never find themselves in a reciprocal relationship with every single person in the public.

The next problem identified by Watley is that stakeholders should be should be considered sooner, rather than later, in the decision-making process (Watley 2000). Identifying and considering stakeholders immediately following the definition stage may encourage decision-makers to emphasize their ethical obligation over the weight of a particular relationship, which has been known to hinder the ethical decision-making process (Miller and Thomas 2005).

The last issue defined by Watley is that obligations should be considered using ethical intuitionism and deontology, rather than a myriad of virtue ethics (Ross 1930; Audi 2004). According to Watley, using self-evident prima facie duties to define obligations would be a more straightforward, practical and readily applicable process, rather than allowing individuals to choose whichever ethical philosophy supports their personal preference or the circumstances at hand. While prima facie duties are not final, they can be used as a guide to determine when it’s better for an individual to perform a particular action over not performing an action. For example, the duty of non-injury explains that, all other things being equal, it is always better to not hurt someone than to hurt someone. Watley (2014) refers to Audi’s (2004) revised list of ten prima facie duties, as outlined in a 2007 review of Audi’s work:

- Non-injury: we should not injure or harm people.

- Truth-telling: we should not lie.

- Promise-keeping: we should keep our word.

- Justice: we should not treat people unjustly and we should rectify and prevent injustices.

- Reparation: we should make amends for our wrongdoings.

- Benefice: we should contribute to the good (the well-being) of other people.

- Gratitude: we should express gratitude to others when good is done to us.

- Self-improvement: we should develop or sustain our distinctively human capacities.

- Liberty: we should contribute to an increasing or preserving the freedom of persons.

- Manner: we should treat other people respectfully (Rovie, 2007; Watley, 2014).

Furthermore, the modified Potter Box allows the decision-maker to consider the weight of value each obligation holds, depending on the stakeholders.

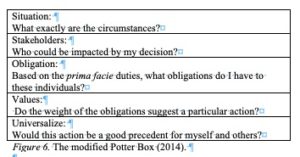

These observations prompted Watley to create what he calls the modified Potter Box (Figure 6).

The modified Potter Box suggests that ethical judgements should follow these guidelines:

- Situation: What exactly are the circumstances? Gather relevant facts and clearly identify any applicable assumptions.

- Stakeholders: Who could be impacted by the decision?Consider all the individuals who could be affected by the decision, both now and in the future.

- Obligations: What obligations do I have to these individuals? Using Audi’s (2004) adapted prima facie duties, identify the duties an individual has to those who are potentially affected. Many of the duties may overlap and, given the circumstances, some duties may not apply.

- Values: Does the weight of the obligations suggest a particular action? Does the good outweigh the bad? Consider not just the number of duties, but the overall significance of each duty. Exercise moral imagination and include trusted others before a determination is made. Look for the most appropriate middle ground that satisfies the most compelling obligation.

- Universalize: Would this be a good precedent for myself and others? Ask if a similar decision would be appropriate under similar circumstances and/or if the decision would be acceptable if the decision maker was instead one of the other individuals affected.

According to Watley, two individuals could be presented with an identical dilemma, but interpret it differently based on their values and principles and what they consider to be their obligations to their stakeholders. The transparency of this modified five-step process, however, would allow “individuals to articulate and discuss the process behind judgment” (Watley 2014, 10).

Due to its early and strong emphasis on consideration of stakeholders, much like the media’s obligation to the public, the modified Potter Box is the most appropriate tool for assessing this case. To the best of the researchers’ knowledge, this is the first case study exploring the use of the modified Potter Box in the field of journalism.

Data Collection and Timeline

Slippery Rock University is one of fourteen universities that comprise the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education. Nestled in Pennsylvania’s tenth legislative district, SRU is home to approximately 8,368 students (King 2018) who receive their community and university information and happenings from student news organizations such as The Rocket. As a whole, SRU encourages its student media to emulate a professional experience, with both editorial and ethical decisions being made by student editors, not university faculty or administrators. Unlike other student media on campus, however, The Rocket is considered independent from the university, as it is only affiliated with, but not owned or operated by, SRU. Over the course of The Rocket’s 80-year existence, the university has supplied a faculty adviser to assist with day-to-day operations, but all final editorial and ethical decisions have always been in hands of The Rocket’s student editor-in-chief and his/her 10-14 person paid staff members. The editor-in-chief position is an annually elected appointment voted on by the previous year’s staff. Cody Nespor, 22, was named editor-in-chief for the 2017-18 academic year

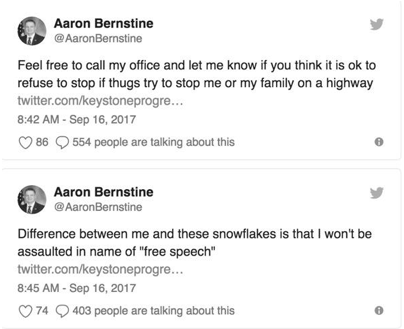

Also strongly affiliated with District 10, which includes portions of Beaver, Butler and Lawrence counties, is Pennsylvania State Representative Aaron Bernstine, 33, a member of the Republican Party. Bernstine assumed office in 2016, defeating his Democratic opponent with a 58.48% vote in his favor. With a background in business, Bernstine is also an adjunct instructor at the University of Pittsburgh. Bernstine was quickly brought to the Twitter spotlight in August 2017 for a response he posted about the non-violent protests in St. Louis, MO. that followed the acquittal of police officer Jason Stockley (Figure 1). Since, the state representative has remained an active and vocal Twitter user. On March 31, 2018, he found himself in a Twitter dispute with The Rocket’s editor-in-chief, Cody Nespor. Below is a timeline of events that led up to the March 31 online confrontation, as well as the outcome of the March 31 tweet. All evidence gathered for analysis was obtained from Twitter and news websites between the dates of March 31 – May 1, 2018.

A. September 16, 2017: Aaron Bernstine posts a response to the August 2017 St. Louis, Mo. protests on Twitter. (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Bernstine’s response to Missouri protests.

After some of his followers commented that they were uncomfortable with his stance on the issue, he used words like “thugs” and “snowflakes” in his responses. See Figure 2.

Figure 2. Bernstine’s response to followers.

In conducting this research, we uncovered that this is not the first time Bernstine tweeted about running over protestors. ThinkProgress reports that on July 15, 2013, Bernstine tweeted that he would refuse to stop his car if he saw the protestors rallying against George Zimmerman. “I’d [definitely] not stop my car! “@NewsBreaker: @Zimmerman protesters have shut down traffic in I880 in Oakland, [California],” Bernstine said (Rupar 2017).

B. September 16 –September 18, 2017: Local and national media outlets such as

the New York Times, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and the Butler Eagle run stories covering the September 16, 2017 tweet (Prose 2017; Rau 2017; Gensler 2018). In an interview with The Times, Bernstine blamed the media and the Democratic Party for exaggerating and “purposefully misinterpreting [his] comments to create social media indignation” (Prose 2017).

C. This tweet not only attracted negative local and national media coverage, but the attention of his fellow politicians, such as Vice-Chairwoman of the Pennsylvania Legislative Black Caucus and State Representative Donna Bullock, who called Bernstine’s tweet unacceptable and recommended that he issue a public apology immediately (PA House 2017).

D. September 20, 2017:

1. The Rocket publishes an editorial titled “Pa House Representative promotes violence by threatening to run over protestors.” The article expressed the staff’s feelings that “no representative should threaten violence on their constituents” (The Rocket Staff 2017).

2. The University of Pittsburgh’s student newspaper, The PittNews, publishes an editorial with the headline “Pitt must condemn professor’s threats.” The piece ends with a recommendation for citizens of Pennsylvania District 10, “when Bernstine is up for reelection, vote against him” (The Pitt News, 2017). To be clear, Bernstine is an adjunct professor at The University of Pittsburgh, but does not represent the Pittsburgh area in the legislature.

E. February 14, 2018: The Parkland High School shooting takes the lives of 17 victims, leaving several more individuals injured.

F. February 26, 2018: NPR reports confirm Trump’s proposal to arm teachers and school staffers (Horsley 2018). While very vocal of his support of the Second Amendment, Bernstine does not acknowledge this proposal on Twitter.

G. February 27, 2018: As the editor-in chief, Nespor writes an editorial in response to the Parkland shooting. In the article, Nespor reacts to the proposal to arm teachers, saying:

“I do not know what the answer is to keep schools safe, but arming teachers is not going to work. My mother is a middle school math teacher; her job is to educate children. She is not a soldier; she should not have to worry about defending her students in a firefight. I believe our goal should be to reduce the number of dangerous situations and to ensure there will be no more school shootings. Arming teachers, who cannot even get enough funding to buy school supplies, would only heighten violent situations and is reactive to stop a school shooting, not proactive in preventing it” (Nespor 2018).

H. March 21, 2018: Bernstine directs a tweet at one of his 1,172 Twitter followers, who had disagreed with him on an earlier Twitter thread, stating, “I don’t typically engage with people on Twitter who have 65 followers.” According to an interview with the Post-Gazette, it was this tweet, which has since been deleted, that prompted Nespor’s March 28 tweet (Behrman and Schackner 2018).

I. March 28, 2018: In response to Bernstine’s tweet, Nespor posts “Every so often I’m reminded of how much an embarrassment for Butler Country having Aaron Bernstine as its rep is” on his personal Twitter account. See Figure 3.

Figure 3. Nespor’s March 28 tweet.

J. March 31, 2018: Aaron Bernstine tweets “Having SRU in my district means I get to work with young college/journalists (they’re the future). There is A++ talent like @Student1 and @Student2* and then there is the “Editor in Chief” of student blog/paper @CodyNesporSRU who pushes a lib agenda and [is] a horrible writer.” This caught the attention of several of Bernstine’s followers, including Hermitage City Commissioner Michael Muha who replied to Bernstine, “Don’t you think it’s beneath the dignity of your office that you [attack] a college student who disagrees with your viewpoints? Or have you given up on the First Amendment entirely?” Bernstine replied to Muha that he does not treat media any different “regardless if they’re 22 or 82. Acting as a non-partisan writer and serving an agenda is wrong on both sides.”

K. Nespor replies to Bernstine’s original post: “Hi Aaron, generally editorial feedback for The Rocket can be sent to my email, xxx1234@sru.edu. But if you insist, I’d be willing to listen to some on here. Care to share any examples of the ‘lib agenda’ I’m pushing? Do you mean this opinion piece where I resist the idea of having to turn my mother into a soldier?”

L. Bernstine replies, “Still trying to figure out what an ‘assault rifle’ is? Put hundreds of rounds through my AR, .45 and .380 in the last week…. and not one person was ‘assaulted.’ Best of luck in your ‘career’ as a ‘journalist’ though.”

M. Nespor replies, “Nice non-answer. I appreciate your support. I’ll be graduating with highest honors in May and I plan on starting graduate school in the fall. ☺”

N. A Rocket staff member joins in and asks, “Aren’t you the guy who equates followers on twitter to intellect, and disregarded someone’s valid point to argue about how many followers they had [?]” Bernstine did not reply.

O. April 1, 2018: Bernstine removes the tweet from his account. However, the conversation was retweeted and continued to catch the attention of other student journalists, advisers, and media professionals across the country.

P. April 4, 2018:

1. The first media coverage regarding the Bernstine vs. Nespor narrative is published on www.journoterrorist.com. The article ended with a call to question who the other two students were that Bernstine mentioned in his original post. The article reads, “both describe themselves as ‘aspiring news anchors,’ and they look like this…” followed by a photo of the young women, concluding with, “which to be clear, isn’t a slam on them. But it is a commentary on the 33-year-old legislator who rates two young blonde women as ‘A++ talent’ – and no other students he represents (Koretzky 2018).

2. College Media Matters posts an interview with Nespor. In the interview, Nespor explains,

“I think this was less of me being a student and more of Bernstine trying to create some sort of him vs the media fantasy,” he said. “The problem is I’m a full-time student, I don’t work for any media outlet outside of school and also I posted my opinion on my own Twitter. I honestly think he just wanted to be Trump Jr. or something and thought I would be an easy target he could construe as ‘the media’” (Lash 2018).

Q. April 6 and 7, 2018: The Butler Eagle and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette publish a second and third interview with Nespor. Nespor explains,

“I really didn’t think too much of it because people get in Twitter fights every day,” Nespor said. “But when I’m at school in Slippery Rock, I am in his district. I live in Slippery Rock nine months of the year. I love Slippery Rock University, I love the town of Slippery Rock and I love Butler County.”

“To see him as the state representative being so juvenile and so dismissive of people on Twitter, I don’t think that represents Butler County very well. I want Butler County to be represented the best it can be, and when I see him acting like a fool on Twitter, that’s not how people in this county are.” (Carr, 2018).

In addition to,

“’If he wants to call me a bad writer or say I push a liberal agenda, that’s OK,’ Mr. Nespor said. ‘I’ve heard that before.’

He said journalists should expect that.

‘But when I’m at Slippery Rock, I’m living in his district. I’m a constituent of his,’ he added. ‘I feel I should be allowed to share my opinion about my representative without a personal attack.’

He said he posted the tweet on his personal account, adding, ‘It’s not like I used The Rocket’s account’” (Behrman and Schackner 2018).

R. Bernstine sends an email response to both news outlets, ultimately using a “fake news” platform to defend himself.

“Facts matter. Whether in news, columns or editorials, even on Twitter, facts actually count. Twitter is not a safe space. While I am a public official, I get tired of the name-calling, the trolling and made-up facts. People, including editorialists — students or professional — have the right to write their own opinion, but they should not resort to personal attacks or made-up facts, if they do, they are substandard journalists” (Carr 2018; Behrman and Schackner 2018.)

S. April 16, 2018: Bernstine is listed as a “loser” in City & State PA’s Winners and Losers for the Week article. The article implies that Nespor should get used to this type of online political confrontation if he plans to pursue a job in journalism (Salisbury 2018).

As displayed through the timeline, all characters within this narrative were faced with several ethical dilemmas. This paper, however, will solely focus on Nespor’s ethical decision-making process as it relates to his response to Bernstine’s tweet, from the perspective of a student journalist and editor-in-chief for The Rocket.

Data Analysis

To reiterate, the purpose of this paper is to apply the modified Potter Box to the ethical dilemma faced by Nespor as it relates to his role as a student journalist and the editor-in-chief for The Rocket. Nespor’s ultimate decision to minimally communicate with Bernstine on Twitter and with the news media will be explored, as well as four alternative options. Following this analysis is a series of recommendations for dealing with the Trump Effect in the future.

The Situation. According to both Potter and Watley, the first step in any ethical decision-making process is defining the circumstances. Without identifying the empirical facts surrounding an ethical dilemma, the other four quadrants cannot be approached (Stiles 2005). Because this is an analysis of Nespor’s ethical action and response to Bernstine’s tweet, the situation should be defined from his perspective. As such, the primary, active individuals involved in this case are Bernstine and Nespor. The secondary individuals are the staff of The Rocket and the two additional student journalists named in the tweet.

The background between Nespor, Bernstine and The Rocket, which can be chronologically observed in the timeline provided, must be understood as it relates to the case at hand before being able to conduct the analysis. With that being said, the background of this situation started with Bernstine’s Sept. 17, 2017 tweet about the protests in Missouri (see Figure 1). In addition to responses from professional media outlets, government officials and another student newspaper, The Rocket wrote an editorial regarding Bernstine’s tweet, calling it “unnecessarily violent.”

No formal communication took place between Bernstine and Nespor until March 28, 2018, when Nespor posted “Every so often I’m reminded of how much of an embarrassment for Butler County having Aaron Bernstine as its rep is” (See Figure 3) to his personal Twitter account in response to Bernstine’s March 21 tweet about refusing to engage with Twitter users who have a small Twitter following.

It was on March 31 that the case at hand truly began, when Bernstine tweeted “Having SRU in my district means I get to work with you college/journalists (they’re the future). There is A++ talent like @Student1 and @Student2 and then there is the “Editor in Chief” of student blog/paper @CodyNesporSRU who pushes a lib agenda and [is] a horrible writer.”

The “made-up-facts” or fake news Bernstine is referring to is unknown. In the following weeks, Nespor was interviewed by College Media Matters, the Post-Gazette and the Butler Eagle. The common theme in his interviews revolved around his overall disbelief that a local government official would attack a student.

The next step is to identify those who could be impacted by the decision. As previously mentioned, Christians, et al. (1998) identify several categories of moral obligation in the realm of journalism: “duty to oneself; duty to clients/subscribers/supporters; duty to the organization at which one is employed; duty to one’s colleagues; and duty to society.” Stiles (2005) notes that the final duty to the public, one of social responsibility, should be at the “forefront in decision-making.” This analysis considers the public and clients/subscribers/supporters, The Rocket, the journalism community and Nespor’s duty to himself, as his stakeholders in this case.

The third step in the modified Potter Box model is to consider the decision-maker’s obligation to each stakeholder, based on Audi’s (2004) adaptation of Ross’s (1930) prima facie duties. As noted by Watley (2014), conflicting obligations will occur in any ethical dilemma, but when considering the modified Potter Box, such conflictions can also provide different viewpoints that could potentially result in alternative outcomes that the decision-maker may miss otherwise. This section will begin with whom Christians, et al. (1998) call a journalist’s number one priority, the public, and continue with obligations to other stakeholders listed in no particular order. Note that every decision-maker has multiple obligations to each stakeholder, many of which are the same. For instance, noninjury, truth-telling, manner and benefice apply to almost every scenario. For the sake of brevity, this analysis will only highlight the top obligation for each stakeholder, before discussing competing values.

With that being said, as the editor-in-chief for The Rocket, Nespor’s primary stakeholders are the “clients/subscribers/supporters” and the public/society at large. Based on the ten prima facie duties, his number one obligation is the truth (Christians et al. 1998) or what Audi (2004) calls refers to as “truth-telling” in his list of prima facie duties. According to Carson (2001), truth-telling includes veracity and the absence of both lying and deceit.

Nespor’s next set stakeholder is the organization at which he is employed, The Rocket. As established, Nespor holds a leadership role with The Rocket, and according to Nesbit (2012) a good leader should be first devoted to consistent self-reflection and self-improvement. Similarly, Audi (2004) speaks about self-improvement in his list of duties, explaining that we should develop or sustain our distinctive human capacities (Rovie 2007). Audi (2004) explains that self-improvement does not refer to “wealth, pleasure or influence,” but to the improvement of our own virtue and intelligence. Such virtues and characteristics include prudence, temperance, justice, fortitude and compassion (Watley 2014). With this being said, Nespor’s top prima facie obligation to The Rocket is self-improvement.

Following his obligation to The Rocket is Nespor’s obligation to his colleagues in the journalism community. All of the prima facie duties apply to the relationship between a journalist and the field of journalism, but Audi’s (2004) promise-keeping is most applicable because of the ethical nature of the field. Codes of ethics, as earlier described using the SPJ, the ONA and the RTDNA, unofficially require a journalist to respect a list of promises, including characteristics such as honesty, accuracy and persistence. Without keeping this promise, a reporter will lose credibility among their colleagues.

According to Christians, et al.’s (1998) list, Nespor’s last obligation is to himself. As explained in a relatable theory developed by Garrett (2004), benefice, self-improvement and other duties that produce long-term, positive outcomes should never override decisions for our own short-term benefit, or those that cause short-term pain for others. With that being said, Nespor’s obligation to himself should have nothing to do with seeking revenge or causing harm. Self-improvement, as listed by Audi (2004), and promoting himself as a student journalist should be considered his top priority in this scenario.

The second to final step in the modified Potter Box model is to consider if the weight of the obligations suggest a particular action, allowing the decision-maker to ultimately choose the most appropriate middle ground that satisfies the most compelling obligation (Watley 2014). As discussed, this includes duty of truth-telling to the public and “clients/subscribers/supporters,” duty of self-improvement to both himself and The Rocket, and the duty of promise-keeping to his colleagues in the field of journalism. In Watley’s work, he encourages the use of moral imagination when exploring available options in a given dilemma. In this case, we conclude that Nespor had five major options. In each of these scenarios, we identify the duty of truth-telling to the public as Nespor’s most compelling obligation. Other obligations, to himself, The Rocket and the journalism community are held at an equal regard.

Nespor’s first option would have been to ignore Bernstine’s tweet entirely. While this option may have put The Rocket at a lesser risk, it would have withheld the truth about Bernstine’s accusation and ethical challenge toward Nespor from the public. The Rocket’s audience deserves to know why the editor-in-chief of their student newspaper is being accused of pushing a liberal agenda, and had Nespor ignored Bernstine’s tweet, long-term, negative effects may have impacted the relationship between the Rocket and the public.

The next option worth exploring would be recommending Nespor to minimally engage with Bernstine directly on Twitter to clarify his accusation, much like Nespor did in reality. Ultimately, this option fulfills what the last option does not, clarifying the basis of Bernstine’s tweet, aka truth-telling to the public. Furthermore, there is no strong argument that this option violates his obligation to his subsequent stakeholders, himself or The Rocket. It could be argued that Nespor’s form of communication carried a certain tone but, overall, his responses, especially in comparison to Bernstine’s harsh comments, were rather tame. Following the interaction with Bernstine, Nespor was contacted by media outlets, as described in the timeline, but he chose to let the story fade shortly after. Because of this, we can conclude that Nespor’s intent was not to seek revenge, but to stand up for his stakeholders. In fact, in an interview with the Post-Gazette, Nespor’s made it clear that his best interest was with the people of Butler County. “I want Butler County to be represented the best it can be” (Carr 2018).

Nespor’s third option would have been to engage in this situation even further than in the last scenario, on both Twitter and in his communication with professional news outlets, and perhaps with more assertion. In consideration of his stakeholders, Nespor could have safely explored this option if his intentions were to advocate for a good cause, such as the negative impact the Trump Effect has on modern journalism and society. However, if Nespor chose this option with a negative intent, for instance, to seek personal revenge to Bernstine’s tweet, he would have immediately violated several prima facie duties to all stakeholders. Altogether, this option is ethically viable if executed properly.

The next option to consider would be for Nespor to reach out directly to Bernstine, whether via email, telephone, but preferably in person, in an attempt to solve the issue entirely. This option would certainly fulfill Nespor’s duty to the public, by confronting the situation head-on and reporting the truth to his readers. This option would also allow Nespor to fulfill his duty to The Rocket, by demonstrating leadership and characteristics that self-improvement. Last, speaking directly with Bernstine would fulfill Nespor’s duty to his colleagues in the journalism community, by playing a role in repairing the “fake news” narrative so commonly told today.

Last, but not least, is an option that is certainly not recommended, but certainly worth discussing as an option: to use The Rocket as a defense on Nespor’s behalf, attacking Bernstine directly. It goes without saying that ethically, this option would not fulfill any moral obligations to any stakeholders. If anything, it does the exact opposite and risks the reputation of all parties involved.

The last step in to consider if the decision sets a good precedent for both the decision maker and others. Of the previously listed options, we would recommend three pathways that could be applied universally. The first is to respond the way Nespor did in reality, confronting the situation head-on, but without revenge. The second would be to take it a step further, and keep the situation in the headlines, advocating for the field of journalism. And last, and perhaps the most ethically-sound, would be for Nespor to reach out directly to Bernstine, in an attempt to discuss and resolve their conflict in person.

Discussion

Overall, the Bernstine vs. Nespor dilemma was avoidable. Based on the facts presented in this case study, several recommendations can be made. First, it is recommended that advisers and instructors expose their student journalists to these types of cases to stress the implications of social media. When a student holds a leadership position such as editor-in-chief, their social media posts, opinions, etc. are subject to ridicule. In fact, we believe that had Nespor refrained from posting his March 28 tweet about his feelings toward Bernstine, this situation may have never happened. This is not to say that students don’t deserve the right to express their values and beliefs, but they need to be wary of the consequences and prepared to face those consequences in doing so, particularly in journalism. Regardless of the account that is used, any social media content is representative of the users’ brand. Additionally, as a trusted information-provider who represents a news outlet, any and all individual opinions, ideas and communication have the potential to impact the reputation of the organization. While Nespor did post on his own account, The Rocket was undoubtedly affected. There have been numerous examples in the last few years of journalists being reprimanded and sometimes fired for posts they make on their personal accounts. In general, journalists should understand that they are always representing their media organization whether they are using their personal account or their organization’s account. In this instance, Nespor was using his personal account. If he had used The Rocket’s account to express his personal dismay with Bernstine, then the subsequent problems would have been exponentially worse. Also, it should be noted that student media organizations are a constant revolving door in terms of personnel. Because of this, student journalists must make decisions that proactively preserve the future of the organization, rather decisions than what would benefit them personally in the short-term. Guidelines for handling situations similar to the one presented in this case should certainly be added to every college media organizations’ operations handbook.

Similarly, politicians and other important figures need to understand the severity of engaging in unproductive banter on social media, in addition to the value of free speech and student journalism. There was not one benefit to the outcome presented by Bernstine’s decision-making process. Unfortunately, because the precedent has been set by the very highest of our government, President Donald Trump, the Trump Effect is bound to continue. Given the amount of immediate backlash to Bernstine’s Tweet and his subsequent backing down, it appears fairly clear that the Trump Effect only works for Trump, and not the typical local politician.

Further, we recommend that the modified Potter Box be used over the original Potter Box, for the sake of considering stakeholders earlier in the process. In the field of Communication, audiences are at the center of successful message transfer and their ability to trust media creators who practice solid ethics is paramount to the survival of journalism. We hope that other case studies are produced utilizing this ethical decision-making model in the future. With that being said, if a student journalist finds themselves in an ethical dilemma in any way similar to the case at hand, it is recommended that the individual use the modified Potter Box to find the solution that works best to create the least amount of damage, both personally and for the student media organization, prior to taking action. The convenience and simplicity of the modified Potter Box makes it easy to measure obligations and weigh options in any given dilemma.

Last, it is recommended that local politics happen on a local level. If faced with this type of situation, we suggest that a student journalist move away from the computer screen and directly contact the politician attacking them and/or accusing them of publishing fake news. There is no need for social media to be the vehicle for democracy. According to the news-democracy narrative (Woodstock 2014), democracy depends on a knowledgeable citizenry and that knowledge stems from news consumption. Rather than miscommunicated information on social media, confronting issues and asking questions should be done during township and borough meetings, rather than through a computer screen.

Conclusion

While these types of situations are unfortunate, they are the reality. It is recommended that college media advisers embrace these types of situations and allow student journalists to make decisions on their own. Advisers can provide students with tools such as the modified Potter Box to aid in the decision-making process, but because of the relatively new nature of social media confrontations in the politics vs. journalism narrative, students need to practice applying these techniques on their own (with guidance) to help them grow as media professionals. Student journalists need to be aware of the current trend of politicians using the media as a means of promoting their own fame and political agenda by deriding them personally and journalism in general. By using the modified Potter Box model, student journalists can avoid being a part of this constructed narrative and act ethically in fulfilling their duty to inform and educate their audiences objectively.

Works Cited

- Audi, Robert. 2014. The Good and the Right: A Theory of Intuition and Intrinsic Value. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Blanchard, Kenneth and Norman Peale. 1988. The Power of Ethical Management. New York, NY: William Morrow and Company.

- Bok, Sisella. 1978. Lying: Moral Choice in Public and Private Life. New York: Random House.

- Bowen, Shannon. 2004. “Expansion of ethics as the tenth generic principle of public relations excellence: a Kantian theory and model for managing ethical issues.” Journal of Public Relations Research 11 (1):65-92.

- Behrman, Elizabeth and Bill Schackner. 6 April 2018. “The Student Called Him an ‘Embarrassment.’ The State Representative Shot Back, Saying He’s A ‘Horrible Writer.’ The Post-Gazette.

- Carr, Andrew. 7 April 2018. “SRU student newspaper editor, state rep. get into Twitter spat.” Butler Eagle.

- Carson, Thomas. 2001. “Deception and withholding information in sales.” Business Ethics Quarterly 11 (2): 275-306.

- Carveth, Rod. 2011. “The ethics of faking reviews about your competition.” Proceedings: Annual Convention of the Association for Business Communication.

- Christians, Clifford G., Mark Fackler, Richardson Rotzoll, Kathy Brittain McKee, and Robert Woods. 1998. Media ethics: Cases and Moral Reasoning, fifth ed. New York: Longman.

- Collins, Terry. 20 Jan. 2018. “Trump’s Itchy Twitter Thumbs Have Redefined Politics.” CNet.

- Daley, Jason. 14 June 2016. “The complicated history between the press and the presidency.” The Smithsonian.

- Fitzpatrick, Kathy. “Ethical Decision-Making Guide Helps Resolve Ethical Dilemmas.” Public Relations Society of America. https://www.prsa.org/ethical- decision-making-guide/.

- Freeman, Edward. 2009. Managing for Stakeholders Ethical Theory and Business, eighth ed. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson.

- Garrett, Jan. 10 Aug. 2004. A Simple and Usable (Although Incomplete) Ethical Theory Based on the Ethics of W.D. Ross.

- Gemperlein, Joyce. 2004. “A renewed focus on ethics at j-schools.” The American Editor: The Bulletin of the American Society of Newspaper Editors 79 (1): 20-21.

- Genseler, Howard. 18 Sept. 2017. “PA Rep. Aaron Bernstine tweets he would run over road-blocking protestors.” Post-Gazette.

- Horseley, Scott. 26 Feb. 2018. “Renewing Call to Arm Teachers, Trump Tells Governors The NRA Is ‘On Our Side.’” National Public Radio.

- Johnson, Jenna. 8 Dec. 2016. “This is what happens when Donald Trump attacks a private citizen on Twitter.” The Washington Post.

- King, Robert. 20 Feb. 2018. “SRU spring enrollment continues upward trajectory,” Press Release.

- Knowlton, Steven and Christopher McKinley. 2016. “There’s More to Ethics Than Justice and Harm: Teaching a Broader Understanding of Journalism Ethics.” Journalism & Mass Communication 71 (2): 133-145.

- Koretzky, Michael. 4 April 2018. “Double-Down Syndrome.” Journoterrorist.

- Lash, Kelley. 4 April 2018. “Politician attacks student editor on Twitter.” College Media Matters.

- Massarella, Linda. 12 May 2017. “Harry Truman once compared the press to ‘prostitutes.’” The New York Post.

- Miller, Diane and Stuart Thomas. 2005. “The Impact of Relative Position and Relational Closeness on the Reporting of Unethical Acts.” Journal of Business Ethics 61 (4): 315–328.

- Mondon, Marielle. 23 April 2018. “Pennsylvania lawmaker calls colleague ‘lying homosexual’ in Facebook rant.” Philly Voice.

- Nesbit, Paul. June 2012. “The Role of Self Reflection, Emotional Management of Feedback, and Self-Regulation Processes in Self-Directed Leadership Development.” Human Resource Development Review 11 (2): 203-226.

- Nespor, Cody. 27 Feb. 2018. “Editorial: Will enough ever be enough? Comments on the Parkland shooting” The Rocket.

- Online News Association. Social News Gathering Code of Ethics.

- PA House. Aaron Bernstine: Pennsylvania House of Representatives.

- Patterson, Philip and Lee Wilkens. 2014. Media Ethics: Issues & Cases, eighth ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Philipp, Beverly and Denise Lopez. 2013. “The Moderating Role of Ethical Leadership: Investigating Relationships Among Employee Psychological Contracts, Commitment, and Citizenship Behavior. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 20 (3): 304-315.

- Potter, Ralph. 1965. “The structure of certain American Christian responses to the nuclear dilemma, 1958–1963.” Harvard University doctoral dissertation.

- Potter, Ralph. 1972. “The Logic of Moral Argument.” Toward a Discipline of Social Ethics, 93-114.

- Prose, J.D. 16 Sept. 2017. “State Representative Aaron Bernstine’s tweet on St. Louis protestors sparks online outrage.” The Post.

- Radio, Television, Digital News Association. 11 June 2015. Code of Ethics.

- Raftner, Kevin and Steven Knowlton. 2013. “Very shocking news.” Journalism Studies 14: 355-370.

- Rau, Phillip. 19 Sept. 2017. “State lawmaker’s tweet brings backlash.” Butler Eagle.

- Ross, William David. 1930. The Right and the Good. Oxford: Clarendon.

- Rovie, Eric. 2007. “Review of ‘The Right in the Good: A Theory of Intuition and Intrinsic Value.” Essays in Philosophy 8 (1), 19.

- Rupar, Aaron. 16 Sept. 2017. “Republican Lawmaker Vows to Run Over Protestors to Block Highways.” ThinkProgress.

- Salisbury, G. 15 April 2018. “Winners and Losers for The Week Ending April 13.” City & State PA.

- Society for Professional Journalists. 6 Sept. 2014. Code of Ethics.

- Shahzad, Khuram and Alan Muller. 2016. “An Integrative Conceptualization of Organizational Compassion and Organizational Justice: A Sensemaking Perspective.” Business Ethics 25 (2): 144-158.

- Smudde, Peter M. 2014. “Focus on Ethics and Public Relations Practice in a University Classroom.” Communication Teacher 25 (3): 154-158.

- Spence, Edward and Brett Van Heekeren. 2005. Advertising Ethics. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.

- Stiles, Siobahn. 2005. “The People vs. Big Business: Applying Potter’s Box to the Ethical Decision to Publish Sex Ads in Newspapers.” Proceedings: National Communication Association.

- The Pitt News Staff. 20 Sept. 2018. “Editorial: Pitt must condemn professor’s threats.” The Pitt News.

- The Rocket Staff. 20 Sept. 2018. “Editorial: Pa. House Representative promotes violence by threatening to run over protestors.” The Rocket.

- Watley, Loy D. 2000. “Practical intuitionism: A modified Potter’s Box tackles advertising ethics.” Proceedings: Society for Marketing Advances.

- Watley, Loy D. 2014. “Training in Ethical Judgement with a Modified Potter Box.” Business and Ethics 23 (1): 2-14.

- Woodstock, Louise. 28 Oct. 2013. “The news-democracy narrative and the unexpected benefits of limited news consumption: The case of news resisters.” Journalism 15 (7): 834-849.