Up Next: An action plan and resources on how to improve diversity opportunities in campus newsrooms. Coming next Tuesday in CMR.

Covering Bigotry on Campus

By Rachele Kanigel

San Francisco State University

Last summer, before they even met, two roommates at Georgia Southern University introduced themselves and started chatting over text. It all seemed friendly until one young woman, who is White*, inadvertently wrote this to her soon-to-be roommate, who is Black:

Last summer, before they even met, two roommates at Georgia Southern University introduced themselves and started chatting over text. It all seemed friendly until one young woman, who is White*, inadvertently wrote this to her soon-to-be roommate, who is Black:

Her insta looks pretty normal not too nig—ish.

The message was intended for a third roommate who was assigned to share the room with them. Mortified, the woman who sent the text immediately apologized.

“OMG I am so sorry! Holy crap,” she wrote. “I did NOT mean to say that. … I meant to say triggerish meaning like you seemed really cool nothing that triggered a red flag. I’m so embarrassed I apologize.”

But the apology didn’t stop the text conversation from going viral. Before long screenshots of the exchange were all over social media.

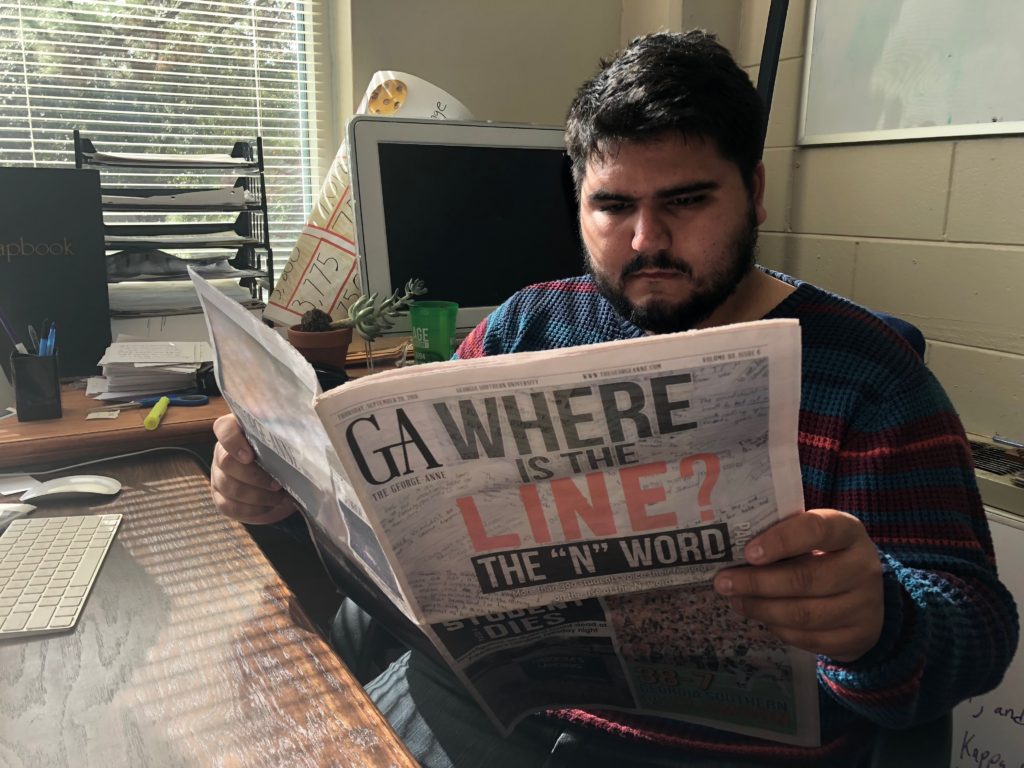

Matthew Enfinger, editor-in-chief of The George-Anne, the student newspaper at Georgia Southern University, recognized the incident as a news story, but also as an opportunity to delve into the deeper issues it represented.

After the newspaper reported on the incident in news articles and an opinion piece, Enfinger mobilized his staff to explore the issue in a new way – through a campus-wide listening project. For several days this fall, members of the newspaper staff tabled at different locations around campus and asked students, faculty and staff to reflect on the N-word and respond to these questions:

- Is the usage of the N-word in private still racism? Why?

- Where do you draw the line on the usage of the N-word?

- Do you think the N-word should be considered free speech? Why or why not?

Participants were encouraged to write their responses on note cards. More than 300 people responded and The George-Anne published all 304 notecards on its website. Photos of the cards were also published in a print edition of the newspaper.

“We’ve had things like this happen before when people used the N word,” said Enfinger, who identifies as half-Hispanic and half-White. “These things happen and then the conversation stops there. We came up with this idea of an article our audience could write. It’s a giant ops piece from our community.”

College campuses are increasingly diverse

The George-Anne’s “Let’s Talk About the N-word Project” was a creative way for the student newspaper to explore some of the intense emotions that are simmering not just at Georgia Southern but at schools around the country.

College campuses today are more diverse than they’ve ever been. In 2015, 42 percent of college students identified as a race other than White, according to the latest data from the National Center for Education Statistics. In 2010, just 37 percent of college students were people of color.

At most schools students from a multitude of racial/ethnic groups, religions, gender and sexual identities, nationalities and political persuasions live, study and socialize together. This makes for fascinating conversations in classrooms and dorm lounges as students learn about cultures and beliefs very different from their own.

But this diversity, particularly set against a national backdrop of political turmoil and cultural strife, can also give rise to misunderstanding and conflict. And student journalists sometimes find themselves covering sensitive issues that would challenge even veteran reporters.

Racial incidents on the rise

Over the past few years, racial incidents and hate crimes have been on the rise nationwide, particularly on college campuses. In 2016, the U.S. Department of Education tracked a total of 1,300 hate crimes at colleges and universities, a 25 percent increase over the previous year. (Between 2011 and 2015, the annual number of hate crimes hovered around 1,000 with little fluctuation.) Hate crimes are defined as offenses motivated by bias related to race, national origin, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, gender or disability.

The text exchange between the Georgia Southern students probably wouldn’t have been counted in these statistics, but once they go viral on social media, even private conversations can roil a campus as much as a swastika or racial slur scrawled on a wall.

Over the past two years the Anti-Defamation League’s Center on Extremism and the Southern Poverty Law Center have collected reports of hundreds of incidents of bigotry on college campuses. Just in the past few months:

- At the University of South Alabama in Mobile a student hung a bicycle and two nooses in a tree outside a campus dining hall.

- Thousands of students, faculty and staff at Vanderbilt University received racist emails from a White supremacist group.

- A Black student at Central Michigan State University found a racial slur “F— u monkey black whores” scrawled on the whiteboard posted outside the dorm room she shared with two other Black women.

- An employee at a student union restaurant at University of North Texas typed the N-word, rather than a customer’s name, on a receipt.

- At Cal Poly San Luis Obispo earlier this year a student was photographed wearing blackface at a fraternity event.

- A fraternity at Syracuse University was suspended last spring after members posted online videos showing one person forcing another to his knees and asking him to repeat an “oath” including racial slurs.

- A pumpkin carved with a swastika and sheets of paper with the words “It’s OK to be white” were found near dormitories at Duke University around Halloween.

In addition, groups such as Identity Evropa and Patriot Front have been distributing fliers and dropping banners on college campuses as a form of activism, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center. A study by the Anti-Defamation League released early this year found a threefold increase in the number of racist fliers, banners and stickers found on college campuses from 2016 to 2017.

“White supremacists are targeting college campuses like never before,” ADL CEO Jonathan Greenblatt said in releasing the report. “They see campuses as a fertile recruiting ground, as evident by the unprecedented volume of propagandist activity designed to recruit young people to support their vile ideology.”

Reporting the news

College media outlets have the job of reporting about these incidents, putting them into context for students who may feel shocked, hurt and scared.

Covering such hot-button issues presents myriad challenges for student journalists. Sources are often unwilling to talk, which can make it hard to present a fair, balanced story. Those who do agree to be interviewed may be emotional or, in the case of university or police officials, unwilling to say more than a stilted prepared statement. And racial incidents often lead to protests, shouting matches and, occasionally, violence.

Amidst the furor, college journalists have to be accurate and fair, dispassionate and unbiased, even if they feel personally touched by the issues being raised.

“As journalists we have to stay clear of being activists,” said Enfinger, The George-Anne editor. “It’s important to be the one reporting the news, not striving for advocacy.”

Overwhelming reaction

Editors reporting on bias incidents sometimes have to handle dozens or even hundreds of letters and comments.

When Golden Gate Xpress, the student newspaper I advise at San Francisco State University, covered a videotaped confrontation about cultural misappropriation between a Black woman and a White man wearing dreadlocks, the newspaper’s website received 131 comments on the original story and dozens more on follow-up stories.

Student newspapers often provide their opinion pages as a forum for staffers and community members to vent about issues, but passionate opinion columns sometimes inflame existing tensions.

In the fall of 2015, at the height of the Black Lives Matter Movement, Wesleyan University sophomore Bryan Stascavage, an Iraq War vet, wrote an opinion column for the Wesleyan Argus criticizing the tactics of some Black Lives Matter activists and questioning whether the movement was legitimate. Noting that he supports the efforts of moderate activists, he wrote: “If vilification and denigration of the police force continues to be a significant portion of Black Lives Matter’s message, then I will not support the movement.”

Within 24 hours, the paper was flooded with online comments and letters to the editor, many of which branded the paper and Stascavage as racist. Some critics accused the paper’s editors, who were overwhelmingly White, of failing to provide “a safe space” for students of color and for abusing their White privilege. Some students dumped stacks of the paper into recycling bins.

A week later, a student group submitted a petition, signed by more than 150 students, alumni and staff, to the Wesleyan Student Assembly calling for a boycott of the Argus and revocation of its student group funding unless demands were met.

The fallout from the column continued for months as The Argus staff successfully fought off two attempts to defund the newspaper. Over the next few months The Wesleyan Argus took steps to diversify the editorial staff by increasing recruitment efforts for minority journalists and dedicating a column to minority voices.

The power of the image

Illustrations, photo illustrations and cartoons about sensitive topics can also hit a nerve. Even when student news organizations try to cover diversity issues responsibly, they occasionally offend people.

In 2015, Cardinal Points, the student newspaper at State University of New York’s Plattsburgh campus, chronicled the growth of diversity at the school with a front-page article entitled “Minority Admission Rates Examined.” The newspaper illustrated the story with a cartoon portraying a Black male with a wide smile and bulging eyes in a cap and gown walking through a run-down neighborhood with a stripped car and graffiti-smeared buildings.

“Great article, but what is this?” a Black male student, pointing to the illustration, said during an interview with WPTZ.

The story quickly went national. The Daily Beast lambasted the publication for printing “the most racist front page in America.”

The editor of Cardinal Points wrote an apology conceding that the cartoon didn’t fit the story and that it unintentionally featured “offensive and stereotypical elements that misrepresent African-American students.”

The incident highlights the importance of student media organizations maintaining diverse staffs and consulting multiple people when covering sensitive issues. It’s hard to imagine a Black staff member wouldn’t have flagged the cartoon had it been passed around for review before publication.

Enfinger said it’s vital that college publications not shy away from sensitive issues even if they are difficult to cover. “I think it’s our duty to listen to our audience and observe our audience. We have to stay on top of these issues, not just let them go away or disappear. If they are impacting your community, you have to cover them.”

* This article follows the guidance of The Diversity Style Guide and capitalizes Black and White when used to refer to races. For more information about that see: https://www.diversitystyleguide.com/glossary/african-american-african-american-black-2/

Up Next: Suggestions on how to improve diversity opportunities in campus newsrooms next Tuesday in CMR.

Rachele Kanigel is a professor of journalism at San Francisco State University and the editor of The Diversity Style Guide, a free online resource with more than 700 terms related to diversity. The book version of The Diversity Style Guide, which includes chapters on covering often underrepresented and misrepresented communities and sensitive issues like suicide, mental illness, immigration and drug use, will be published by Wiley in January 2019. Sections of this article were taken from The Student Newspaper Survival Guide by Rachele Kanigel.