Public officials cannot block naysayers from social media

By Carolyn Schurr Levin

The campus quad is a place where students, professors, administrators, staff, and visitors talk, walk, congregate, share ideas, play catch, hawk college newspapers, and so much more. It is a space that has traditionally been open and accessible, with few limitations, not only at public universities, but also at private colleges. In many respects, it is similar to a traditional town square, the open space in the heart of a town where people gather, share thoughts and are entertained.

Because they are open to all, town squares are, by law, considered to be traditional public forums which are given the highest level of First Amendment protection. They are public places that have by long tradition been devoted to speech and assembly. The government has a difficult time limiting speech in such spaces.

A public forum has traditionally been a physical place. But, in the 21st century, we interact in new digital types of public squares. On Twitter, Facebook and other social media platforms, we meet virtually, instead of in person, to share and debate ideas. Although we don’t throw a Frisbee disc as we do on the campus quad, we toss out our opinions to our virtual communities. What happens then, if public officials try to limit us from access to that online space because they don’t like our opinions? Can they do that? Or is that similar to telling a student that he can’t express his ideas to his friends while traversing the campus quad?

A recent case is winding its way through the federal courts on this very issue. When U.S. President Donald Trump blocked users who had criticized him on his @realDonaldTrump Twitter account, the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University joined with several blocked individuals in filing a federal lawsuit, claiming that Trump’s Twitter page is a digital town square where individuals cannot constitutionally be denied access. “The @realDonaldTrump account is accessible to the public at large without regard to political affiliation or any other limiting criteria,” the 2017 lawsuit stated, arguing that the blocking of users violated the First Amendment.

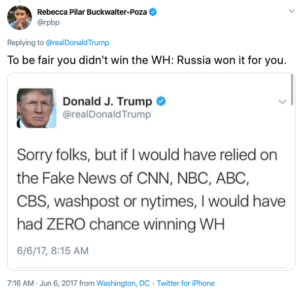

Rebecca Buckwalter-Poza, a writer, had replied to one of the president’s tweets in 2017,“To be fair you didn’t win the WH: Russia won it for you,” she tweeted. Soon thereafter, she discovered she had been blocked from the @realDonaldTrump account.

Rebecca Buckwalter-Poza, a writer, had replied to one of the president’s tweets in 2017,“To be fair you didn’t win the WH: Russia won it for you,” she tweeted. Soon thereafter, she discovered she had been blocked from the @realDonaldTrump account.

Philip Cohen, a sociology professor at the University of Maryland, had replied to one of the President’s tweets with a tweet showing a photograph of the President with these words superimposed on the photograph: “Corrupt Incompetent Authoritarian. And then there are the policies. Resist.” About 15 minutes later, he discovered that he too had been blocked from the @realDonaldTrump account. Buckwalter-Poza, Cohen and several other Twitter users joined with the Knight Institute in arguing that by blocking them from his Twitter account, the president has engaged in viewpoint-based discrimination that violates their First Amendment rights.

Philip Cohen, a sociology professor at the University of Maryland, had replied to one of the President’s tweets with a tweet showing a photograph of the President with these words superimposed on the photograph: “Corrupt Incompetent Authoritarian. And then there are the policies. Resist.” About 15 minutes later, he discovered that he too had been blocked from the @realDonaldTrump account. Buckwalter-Poza, Cohen and several other Twitter users joined with the Knight Institute in arguing that by blocking them from his Twitter account, the president has engaged in viewpoint-based discrimination that violates their First Amendment rights.

A federal district court judge agreed with them. On May 23, 2018, U.S. District Judge Naomi Reice Buchwald decided that Twitter’s interactive space is a designated public forum and the viewpoint-based exclusion of individuals violates their First Amendment rights.

The case didn’t end there, though.

The president appealed that decision on June 4, 2018. In a 3-0 decision about a year later, on July 9, 2019, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirmed the district court’s holding that Trump’s practice of blocking critics from his Twitter account violates the First Amendment.

“The First Amendment does not permit a public official who utilizes a social media account for all manner of official purposes to exclude persons from an otherwise-open online dialogue because they expressed views with which the official disagrees,” the appellate court held.

The appeals court decision did not end the case though. On Aug. 23, 2019, the president filed for a “rehearing en banc,” asking the full Second Circuit Court of Appeals to decide that the three-judge appeals court panel got it wrong. That petition for a rehearing is still pending, six months after it was filed.

Lest you think that the issue of blocking critics online is a partisan one, on the same day that the appeals court decided the Knight Institute v. Trump case in favor of the blocked Twitter users, two different Twitter users sued U.S. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez for blocking them from her @AOC Twitter page because of their opposing political views. Dov Hikind, a former Democratic state assemblyman from Brooklyn, New York, frequently criticized Ocasio-Cortez on her Twitter page. “If the courts ruled POTUS can’t block people on Twitter, why would @AOC think she can get away with silencing her critics?” he asked on Twitter. The second plaintiff, Joseph Saladino, a YouTube personality known as “Joey Salads,” who was also blocked by Ocasio-Cortez, said his separate lawsuit was a test of whether there is a double standard in the courts for liberals and conservatives.

Shortly after the two federal lawsuits against Representative Ocasio-Cortez were filed, she apologized, settling at least one of the cases. “In retrospect, it was wrong and improper and does not reflect the values I cherish,” she said in a statement about her settlement with Hikind. “I sincerely apologize for blocking Mr. Hikind.”

Turning back to campus, then, we already know that students cannot be stopped from speaking on the quad or from posting club notices on campus bulletin boards that are open to all. So, can a university president or other college administrator remove comments or block users on his or her social media site because those users criticized university policies or decisions? The Knight Institute v. Trump case seems to indicate that, at least for an administrator at a public university, the answer to that question is a resounding no.

Carolyn Schurr Levin is a media and First Amendment attorney affiliated with the New York City Law firm of Miller Korzenik Sommers Rayman LLP. She was the vice president and general counsel of Newsday, vice president and general counsel of Ziff Davis Media, and media law adviser for the School of Journalism at Stony Brook University. She has taught media law at Baruch College, Stony Brook University, Long Island University, and Pace University. From 2010-2019, she was the faculty adviser for the Pioneer, the student newspaper at Long Island University, during which time the Pioneer won 28 awards.

RELATED STORY:

“Public Officials Can’t Block Critics from Official Social Media Accounts”