By Daniel Reimold, Ph.D.

University of Tampa

Who owns the content published by campus media: the outlets that publish it or the students who create it? What should you do when sources want to review their quotes? What are the ethics of email interviewing? And how do you determine when content is controversial or graphic enough that readers deserve a warning?

Throughout the past calendar year, the student press faced these ethical questions and a number of others. Some were especially intense. Others were multimedia-specific. And still others played out in real time.

Throughout the past calendar year, the student press faced these ethical questions and a number of others. Some were especially intense. Others were multimedia-specific. And still others played out in real time.

The quandaries, debates and ultimate decisions serve as potential roadmaps for other student staffers and advisers who may deal with similar dilemmas in 2013.

In that spirit, here is a sampling of student press ethical scenarios or decisions in 2012 worth mulling over. The bottom line: In each case, with the facts presented, how would you respond?

The Bear Photo

Late last spring semester, a student journalist’s photo of a tranquilized bear went viral—and almost spurred a lawsuit.

In April, Andrew Duann, a student photographer for The CU Independent, snapped an instantly-iconic shot of a brown bear falling from a tree near a University of Colorado residence hall village. The bear had been tranquilized by local wildlife officials and was subsequently taken into custody for its own—and others’—protection. The photo almost immediately became a web sensation.

In April, Andrew Duann, a student photographer for The CU Independent, snapped an instantly-iconic shot of a brown bear falling from a tree near a University of Colorado residence hall village. The bear had been tranquilized by local wildlife officials and was subsequently taken into custody for its own—and others’—protection. The photo almost immediately became a web sensation.

And then came a post-viral twist: In the wake of the photo’s online success and its republishing by other news outlets, Duann temporarily looked into legal action against his own paper. As Poynter’s Andrew Beaujon reported, Duann was “upset that the paper’s adviser . . . allowed publications around the world to reproduce the photo, asking most outlets only for it to be credited to Duann and the CU Independent.”

Duann considered the bear shot his personal copyrighted property, even though he is on the paper’s staff and apparently supplied it willingly for the story it accompanied. Reporters and photographers are not paid at the Independent, and Duann told Beaujon he had not signed a contract outlining his specific rights in cases like this.

The Decision: Duann and the Independent apparently settled the matter in-house, without a lawsuit.

The Rape Victim

Also in April, The Comment at Bridgewater State University faced “an angry backlash” from its readers and the BSU administration for naming a rape victim in a published piece.

The controversial article was a straightforward recounting of a student’s past sexual assault, a story she shared with 200 participants at a campus “Take Back the Night” rally. It identifies the student by first and last name and provides additional details about her alleged attacker and the timing and location of the assault, all of which she stated publicly at the rally or was uncovered through a basic web search.

Vigorous debate ensued. As one student said at a BSU SGA meeting, “This is ethically and morally unacceptable and it needs to be changed. I do understand and respect the freedom of press, but a victim’s right of privacy and safety needs to be foremost and be protected.”

The Decision: Comment editors declined requests to apologize or take down the article or the student’s name from its website. As they argued, “The Comment doesn’t publish the names of sex crime victims without their consent. But there is implied consent when someone speaks in a public forum, and . . . the whole meaning of the rally was to encourage victims of sexual assault to speak up and not live in shame.”

The Anti-Muslim Ad

In July, editors at The Collegiate Times at Virginia Tech published a controversial advertisement in a summer print edition.

The so-called FLAME ad, created and distributed by the non-profit organization Facts and Logic About the Middle East (FLAME), pushes what many agree is an anti-Muslim agenda. Among other “facts” and perspectives, it purports there is rampant anti-Semitism and Holocaust denial within the Muslim-Arab community. It also chides the news media for failing to properly report upon the “outright ethnic cleansing” of Christians by Islamic radicals.

The so-called FLAME ad, created and distributed by the non-profit organization Facts and Logic About the Middle East (FLAME), pushes what many agree is an anti-Muslim agenda. Among other “facts” and perspectives, it purports there is rampant anti-Semitism and Holocaust denial within the Muslim-Arab community. It also chides the news media for failing to properly report upon the “outright ethnic cleansing” of Christians by Islamic radicals.

The Decision: After the ad’s publication, editors felt compelled to reach out to readers, explaining the paper did not support the content. In an online letter, CT editor-in-chief Michelle Sutherland confirmed that while staffers don’t agree with the ad’s “underlying message of cultural hatred . . . the CT is totally dependent on advertising revenue. We receive no financial support from the university. It is not as simple as saying, ‘We do not support this message, and we will not collect your money.’ We exist solely because people pay us to get their message out– especially in these economic times.”

Not all readers bought this financial excuse. As one commenter asked Sutherland beneath her note, “So you’re saying that you essentially whore out ad space to anyone who wants it? Glad to know you’re that desperate.”

The Autopsy Tweet

In August, The Oklahoma Daily upset and enraged some readers at the University of Oklahoma for temporarily posting a deceased student’s autopsy report online. The report was linked in a Daily tweet and later a story that revealed new details about the student’s death.

The trouble began when Daily staff learned a female senior student had been legally drunk in June when she fell to her death from an OU administrative building. That potentially significant detail was included in an autopsy report prepared by a state medical examiner. While outlining the specifics of the student’s blood alcohol level on the night of her death, the report also included intimate details about her underwear, genitalia and menstrual cycle and a very graphic accounting of her injuries.

A large block of readers described the paper’s decision to share the full report as distasteful and unethical—airing private information without enough accompanying news value and causing additional hurt to those who knew and loved the student. As an OU alumnus wrote in a letter to the editor, “Take a moment to consider the [student’s] family who is still grieving after the loss of their daughter and the friends who have to read that trash you call journalism. That information does not benefit the public in any way, shape or form.”

The Decision: While legally within its rights to post the document, the paper subsequently apologized and pulled the report from its website.

The Email Interview

Editors at The Daily Princetonian had grown dismayed at the “prevalence of email quotes” appearing in stories. Top staffers at the Princeton University student newspaper felt these e-quotes had become detrimental to the newspaper’s journalistic mission.

As editor-in-chief Henry Rome argued, “Interviews are meant to be genuine, spontaneous conversations that allow a reporter to gain a greater understanding of a source’s perspective. However, the use of the email interview—and its widespread presence in our news articles—has resulted in stories filled with stilted, manicured quotes that often hide any real meaning and make it extremely difficult for reporters to ask follow-up questions or build relationships with sources.”

The Decision: In September, after “consultations with major national news organizations’ senior editors and reporters,” Rome announced the paper would no longer publish quotes submitted by email in its news stories.

The Quote Review

For a number of years, The Harvard Crimson had allowed Harvard University officials to review and change their quotes prior to publication. The result of this longstanding practice, editors increasingly recognized, was a culture of decreasing candor and availability among Harvard staff sources.

As Crimson president Ben Samuels wrote in a memo to staff: “Some of Harvard’s highest officials—Including the president of the university, the provost, and the deans of the college and of the faculty of arts and sciences—have agreed to interviews with the Crimson only on the condition that their quotes not be printed without their approval. As a result, their quotes have become less candid, less telling, and less meaningful to our coverage. At the same time, sources have more and more frequently agreed to communicate only by email rather than in person or by phone, or have asked that their names not be used along with their comments.”

The Decision: At the start of fall semester, Crimson editors announced it was no longer allowing quote review. In a letter to readers, Samuels and managing editor Julie Zauzmer confirmed that the new Crimson policy restricts “reporters from agreeing to interviews on the condition of quote review without the express prior permission of the president or the managing editor.”

The Funny Football Tweets

In October, athletics officials at New York’s Stony Brook University threatened the press credentials of a student magazine in response to a staffer’s comedic live-tweeting of a football game.

During homecoming weekend, The Stony Brook Press, a biweekly magazine at SBU known for its mix of serious and satiric content, covered the SBU football team’s one-point win over Colgate University. A pair of photographers captured shots from the sidelines. A reporter worked on a serious recap from the press box. And a separate staffer sat in the stands, live-tweeting the action on the field in humorous fashion.

The staffer sent tweets like “Stony Brook gets stuck in the sand trap and Colgate wins their first power play.” As the Press explained, “His objective was to live-tweet the game, while making references to any sport but football. . . . If anything, we were poking fun at our lack of knowledge when it comes to sports.” SBU officials were apparently not amused, threatening to revoke the magazine’s press credentials for the rest of the year unless it started tweeting correctly.

The Decision: The Press fought back against the threats. In an editorial about the incident—headlined “Don’t Censor Me, Bro!”—editors clarified that the tweeting staffer had not attended the game using an SBU-issued press pass. As the editorial stated, “In many ways, the Athletics Department was overstepping their boundaries by doing this. First of all, under the First Amendment, we have the right to publish anything we want, even tweets. . . . Technically, if we don’t cover a sporting event in a manner that the Athletics Department deems appropriate, it has the right to take back the press credentials they issued to us. But that doesn’t make it right.”

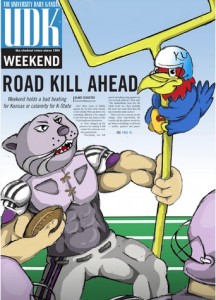

The Road Kill Battle

The University of Kansas football team had a rather dreadful season in 2012. According to the team’s head coach Charlie Weis, outside media are allowed to express this opinion with impunity. But the school’s student newspaper, The University Daily Kansan, is not.

In early October, Weis ranted on Twitter about what he felt was unfairly harsh coverage in the Kansan about the football team’s many woes. He particularly took issue with preview coverage of the squad’s mid-season game against in-state rival Kansas State University. The full-page cover graphic in the Kansan kicking off the coverage displayed a tiny, fearful Jayhawk hugging a goalpost, while a large, muscular KSU Wildcat races fearlessly toward the end zone. The accompanying story’s headline: “Road Kill Ahead.”

In early October, Weis ranted on Twitter about what he felt was unfairly harsh coverage in the Kansan about the football team’s many woes. He particularly took issue with preview coverage of the squad’s mid-season game against in-state rival Kansas State University. The full-page cover graphic in the Kansan kicking off the coverage displayed a tiny, fearful Jayhawk hugging a goalpost, while a large, muscular KSU Wildcat races fearlessly toward the end zone. The accompanying story’s headline: “Road Kill Ahead.”

In a tweet posted to his personal account @CoachWeisKansas prior to the game, Weis shared, “Team slammed by our own school newspaper. Amazing! No problem with opponents paper or local media. You deserve what you get! But, not home!”

The reaction, and the subsequent furor and media attention surrounding it, sparked a debate about how student journalists should approach coverage of their own school’s sports teams.

The Decision: The Kansan continued to cover the team aggressively and objectively. As Kansan columnist Mike Vernon wrote, in the wake of the incident, “Kansas is a public university, and it has a damn good journalism school that is here teaching its students to be objective members of the Fourth Estate of the United States of America, to hold its leaders accountable, and to be a free and independent press. . . . [T]he Kansan isn’t here to rally up student support for the football team. . . . Students at this university deserve better than a pom-pom squad of a newspaper. They deserve to get the truth.”

Daniel Reimold, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of journalism at the University of Tampa, where he advises The Minaret student newspaper. He maintains the student journalism industry blog College Media Matters. His book Journalism of Ideas: Brainstorming, Developing, and Selling Stories in the Digital Age is being published in April 2013 by Routledge.