Campus media can tell stories of Muslims in ways that help build better understanding of life for these students

By Michael A. Longinow

Biola University

Syed Rizwan Farook walked the campus of California State University in San Bernardino like any other student. Friends remember him as quiet but friendly. He was smart. He finished high school early by testing out of requirements. He made the dean’s list at CSUSB and earned an undergraduate degree in 2010 in environmental health, according to the campus university’s newspaper. But five years later, he and his wife, a woman he’d met on a Muslim pilgrimage in the Middle East, took automatic weapons into a holiday party at a county services building and killed 14 people, wounding 21 others before being killed themselves in a gun battle with police, according to the Washington Post.

Newsweek called this young man and his wife “Terror’s New Face.” Each had, in their own way, taken center stage as a “homegrown extremist.” And the result, on college campuses, was a renewed set of fears about danger and risk from students based on what they look like, what they believe, and where they — or their family — grew up, according to coverage Dec. 5 in the Chronicle of Higher Education.

Can campus media stop radicalization of Muslims on their campuses, or nearby? Can it, all by itself, bridge the chasms of suspicion between Muslim students and those on American campuses nationwide? Probably not. But it can tell the stories of Muslims in ways that help build better understanding of life for these students. And the time for that is now — or yesterday.

There is no easy fix for campus newspapers to report on, write about, and provide ongoing coverage of Muslims in the Post-San Bernardino era. And the steps might seem easy. What makes them difficult is more a matter of the mind and heart than of technique.

Campus editors and their staffers have to begin with seeing there’s a problem. If they do, they’ll be leading the way in American media; professionals looking to hire them aren’t doing well with this according to a study by Travis Dixon and Charlotte Williams last year in the Journal of Communication — a follow-up of another study in 2009 by Oliver Hahn and Julia Lonnendonker in the Journal of International Press and Politics.

Joyce Davis, then a deputy foreign editor with Knight-Ridder, warned of the problem 12 years ago, in a plea for Poynter.org. “Muslims complain that because American journalists know so little about Islam,” she wrote. “They frequently quote ill-informed people or people misusing the religion to promote their own narrow agendas.” Davis is now a media consultant and president of the World Affairs Council of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Poynter is still one of the few voices speaking for change in how newsrooms approach this type of coverage.

Improvement can begin anywhere, but this article will suggest it begins with the interview — but not the simplistic kind. Student journalists have to learn to get outside themselves, and get over themselves. It’s about encounter. And it takes practice, patience, and preparation.

We’ll take those in reverse order. Suggestions for this article come from a course at Biola University in Southern California in which students are required to tell a story based around a person whose first language is not English, who was not born in the United States, and whose religion or faith background is completely different from the student’s.

That story becomes a two-part feature article series that requires sights, sounds, smells, textures and context — lots of cultural explanation and illustration. Photos, video or audio are optional, but interviews must be recorded and transcribed to ensure accuracy. Three interviewed sources are required for each story in the series (one primary, two supplemental, all must be quoted using full names.) But the admonition is that the more sources a reporter talks with, on the record or off-record, the deeper, richer and more thorough will be the story.

The course does not teach them about how to repurpose political rhetoric or pitch stories about who’s angry at whom based on inflammatory words, actions or reactions. It’s about helping student journalists tell stories about what it’s like to be Muslim in a campus context that very often doesn’t understand what that means.

Preparation Start with you.

The interview encounter will be a journey into another culture. But before it begins, the journalists in the project are required to write a paper probing their own culture. They have to trace their ethnic heritage as far back as they can. Nobody is allowed to say “I’m just white” (or just another color.) It’s first-person, expected to get personal.

Another part of the paper is description of how the student’s upbringing involved encounter with people of other races. And they’re prompted especially to think back to instances where encounters were harsh, unkind, obtuse, painful for them ,or for people they knew. It’s a tried and true method according to studies of diversity discussion by Peter Frederick in the journal College Teaching in 1995, and a study last year by Ann Marie Gunn and James King on diversity discussion in preparation of educators in the journal Teacher Development.

Media advisers who don’t teach classes might draw the same result in a long meeting. (Provide food and block out a couple hours.) What happens is the opening of a door in student journalists’ minds into what culture means. By beginning with their own cultural journey, students become ready (or get closer to ready) for interviews with people whose journey has been made difficult.

Begin with interpreters

Before a journalist can approach someone of another culture, particularly one with reason to distrust them, it’s best they to talk to people who can help them understand the very premise for the article. If a student has friends or family who are Muslim, they might begin with them. Bringing such cultural interpreters into class is a good first step. A panel is even better. For media advisers, it could begin with bringing the cultural interpreters into a meeting with editors. That could be in the newsroom, or better yet a local Islamic Center or community library conference room.

Some of the interpretation might be of language. If the most important person in your story speaks Arabic better than English, don’t let students muddle through it on their own. Direct them to a language interpreter. Dave Kaplan, an author and investigative reporter, cautions that you need someone fluent not just in the language but in its cultural usage. They need to know how to explain slang, euphemisms and figures of speech, according to interviews with cross-cultural journalists by Lori Luechtefeld in IRE Journal in 2003.

Students in this project often begin the first story of the series thinking the interpreters aren’t necessary. By the second story, they know better. Research in Journalism Educator by Sharon Bramlett-Solomon, in 1989, showed that the resulting interviews are deeper and provide more detail.

One student of mine who went to an Arabic interpreter found he knew of a business owner who did eyebrow threading out of her home. She wouldn’t meet with the student in public, but let the student come into her living room. When the student asked for the woman’s name for the story, it got quiet. There was Arabic exchange with the interpreter. The woman said she couldn’t give her name because she was an asylee. She had real fears about her safety if her name got into a story.

Read, watch and listen

Even the best journalism is, by its nature, derivative. Your students aren’t the first to try this. Some have done it well; others have botched it. Have them check out prior coverage of this person or their region of the city or state. The first time I taught this course, I had student journalists do an in-depth business profile. The real story was a person, but it was also their donut shop, their bakery, nail salon, or restaurant. When students found out that a certain ethnic group predominated ownership of nail salons in our part of the state, the perspective helped their coverage.

Another semester I had students focus on schools, children of immigrant families, and how much “being smart” or “success” were to kids in those families. The more the students read up on the culture and how education matters to that culture, the better were the questions. (I also had them read The Smartest Kids in the World and How They Got that Way by Amanda Ripley, a journalist who had dug deep in global cross-cultural storytelling. Her in-depth approach showed my students that real people dig deep the way I was saying they should.) For advisers, one way to get your staff thinking about this is to have them analyze coverage they see online. Have them pull it up in a newsroom meeting. (To really get them jazzed, have them pull up coverage from competing campus media.) Talk about what worked and what was generalization or culturally superficial. Talk about how to get a better story on your campus or nearby.

Patience Take the time

Invariably, a roomful of campus editors will sit around the room and talk about how important this story is and give it two weeks. For a daily, that might seem like a long time. But for a newspaper or media outlet that’s never done a cross-cultural story, or that’s done one that didn’t go well, time is crucial. Help students respect the complexity. And remind them that in some cultures, hurry isn’t part of the equation — particularly when someone not of their culture is asking questions. This could be the kind of story a staff plans starting in September and runs in February. Do it right, running not just the story (or stories), but charts, sidebars, timelines. Photos and maybe video that’s appropriate and helps explain well.

Relationship first, tools later

The power of encounter is person-to-person, eyeballs to eyeballs, in the same space. True, it’s not journalism until it’s in a form that can be conveyed. But the student’s first approach might be better with no notebook or pen and definitely no camera, tripod, lights or audio gear, according to a study in 2006 by Nancy Graham Holm for Journalism & Mass Communication Educator.

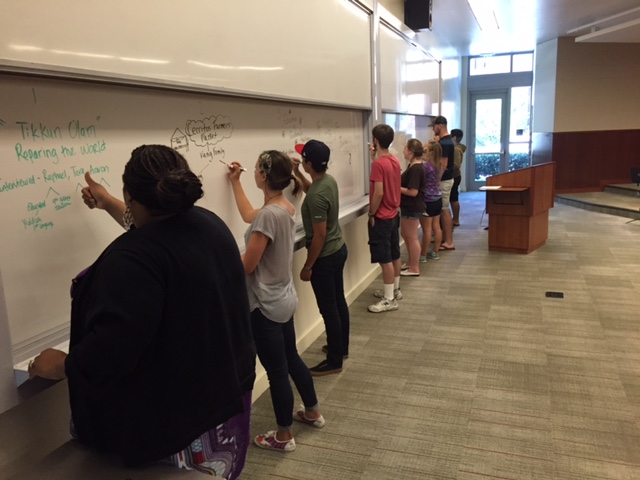

What we did in class was to have the students interview a cultural interpreter. He stood up front and fielded questions. Early on, we also took part of a class session and students went out to chat up those on campus (Asian, African-American, Middle Eastern) to ask their thoughts about a recent news event that affected that group. One student in the class called it profiling. I called it dialogue. And the students learned that people don’t mind talking, particularly when the student asking shows genuine interest in learning. They learned awkward isn’t in the asking. It’s asking badly. Media advisers who don’t have class time per se, could encourage a staffer (or staffers) to start on a smaller cross-cultural story as practice before diving into a bigger profile piece.

Expect to feel stupid

Students who try will make mistakes. All the preparation won’t help when, in the interview moment, they get flustered or distracted and say something that sounds uninformed or could offend. The answer is not just more words — ignoring what happened. Awkward as it is, the answer is apology. Hopefully it won’t mean shutting down the interview and starting over another time (though that might be needed.) Your student is a visitor, in some sense, an intruder. The source — like any source for any story — has no reason to help her. Unless so persuaded, the source has no vested interest in the student’s getting it right. In fact, they half (or fully) expect her to get it wrong. Humility can win over some of the toughest sources.

When you’re turned away…

Majority culture students are often miffed, tempted to walk off in a huff, when they approach a minority culture person and get rejected (maybe harshly.) Sources from another culture have lots of reasons for anger that rises fast when a journalist approaches. It could be they were misquoted — or somebody they care about was. Maybe badly done mainstream media coverage is flashing in their mind. It could be the topic brings back moments that hurt, maybe deeply — a phenomenon noted by Kate Wright in Journalism in 2012.

Or, more simply, the student journalist wasn’t smart about the approach: The source was busy; they were surrounded by people who could be critical if they talked to a journalist.

The answer might be perseverance. Send them back. Get them to try again. Or it might be time to try another source. But this cross-cultural story need not be over because a source wouldn’t talk. It is smart, though, to learn what went wrong. (The cultural interpreter might be where to go for some insight.)

Ask well, and follow up.

Students doing this project learned that when they went into a cross-cultural interview with no prepared questions, they regretted it. Campus journalists get away with “winging it” too often. On-campus sources will pour the story out with barely an invitation. What students learn with this project is that the best questions come from their reading, from prep talks with the interpreter, maybe from having been turned down by someone because questions were unclear or came off as culturally offensive.

Students also learn (again) that vague is bad. When a cross-cultural source speaks a generality, or gives a passing reference to something, it’s not time to move on. It’s time to stop and go back. Research in 2010 by Kroon & Eriksson in Journalism Studies suggests that’s also about patience and humility.

Questions that show the student journalist has done her homework are sometimes an opening into a deeper story. Some cross-cultural sources will be impressed that the journalist talked to every other Muslim shop owner in the plaza; they’re interested in what those peers had to say about the shop owner’s success. (Be warned, this isn’t always the ticket to easy interviewing; name-dropping without genuine interest can smell like schmoozing in any culture. When the student journalist communicates genuine interest, real curiosity, the backgrounding comes off as icing on the cake.)

Practice — Go before you go

In one semester, one of the bolder of my students donned a hijab (which she scouted out and found at an Arabic clothing store) and visited a local mosque for women. She didn’t get a lot of questions answered, but she gained perspective that made later interviews more vivid. Arabic culture, up close, gave insight that no amount of reading or video watching could equal. Student journalists who have never been the only Caucasian in an Arabic grocery or restaurant need to do that before they get far into their research. The tendency to be awed by cultural difference diminishes when the reporter has been around that difference a few times (better yet, a lot of times.)

Write before you write

Drafts are the key to good writing. But the urban legend is that brilliant journalism just happens — typically in the waning moments before deadline. It’s hooey. Profs know it; media advisers know it. But on stories like this, it’s crucial that student journalists put the piece together early. That’s so they can tear it apart, rewrite the lead, hack out paragraphs that don’t help, and go back for more information. It could be that the whole piece needs to start over, maybe with better sources.

Don’t do this just once

One of the common frustrations of cultural minority groups is journalists who parachute into a situation or event, cover it (maybe badly), then disappear — instantly losing interest in the people they persuaded to go on the record. As a professor, make it your ambition to keep teaching and guiding such that cross-cultural story coverage continues in ever improving ways. Advisers can counsel their editors that to really be thorough about telling the story of Muslims on your campus, the answer is coverage that continues in a patient, observant and culturally insightful way.

Michael Longinow is faculty adviser of The Chimes, an independent award-winning weekly and daily online newspaper serving Biola University in Southern California. Prior to advising at Biola, he was faculty adviser to The Collegian, another award-winning student weekly serving Asbury University in Central Kentucky. Longinow has covered politics, business, crime, civil rights issues and urban development in Illinois and Georgia. The product of Mexican and Ukrainian roots, Longinow grew up in the Chicago area where diversity struggle and the deep-seated conflicts born of racism were deeply imprinted on his mind. Longinow holds a bachelor’s degree in political science from Wheaton College (IL) where he served on Wheaton’s campus weekly; he holds a Master of Science in editorial journalism from the University of Illinois-Urbana (where he served on the Daily Illini), and earned a Ph.D in educational policy studies with a cognate in journalism history from the University of Kentucky.