Their Voices Are Green: An Analysis of Environmental Themes

in College Magazines 2018–2022

Abstract

Campus magazines are tasked with producing content to serve and reflect the lifestyle of their campus and community. But, student magazine editors redefined “campus culture” in content choices, as life outside campus changed amid culture wars in 2018, a mass shooting in a Florida high school, historic floods and wildfire, a global pandemic, the Sunshine Movement and COP26. Through these historic events, editors – particularly in Editor’s Note – chose to use their voices to redefine “campus culture” and call for their generation to live with intention and accountability.

Editions from three nationwide contests were sampled 2018-2022 to examine environmental content focusing on three variables: Cover, Table of Contents, and Editor’s Note. Prominent themes that appeared through semiotic analysis are climate change; policy; food; distribution / system; fashion: art / beauty; solutions; activism; pollution; hazard / crisis weather; conservation; sustainability. A review of 55 publication and 135 elements shows climate change, solutions, and activism dominate discussion, with editors introducing content in more than half their columns not found in edition content. Cover art results show 59% contained some environmental element while Table of Contents amplified environmental content with 61% . Framing was measured by how creators located their content: how is their commonsense of environment defined: as a global, local, or campus intent? Results show writers based their environmental concern on campus than in urban environments, while analysis of institutions shows private colleges produced the majority of environmental content.

Key Words: Environment, Campus Media, Magazine, Semiotic Analysis, Framing

Introduction

This research study analyzes award-winning college magazines 2018–2022, specifically focusing on discourse and content of environmental themes during recent unprecedented times: severe and historic global weather events; a new decade spurs generational calls to eco-activism; the COVID-19 pandemic prizes a clean environment as civil rights; COP 26 gathering generates Gen Z and youth participation in record numbers.

One objective was to extend earlier work tracing content changes found in three elements of campus magazines 2018–2022 (Terracina-Hartman, 2024). This study selects a subset of dominant themes to further assess the framing, presentation, discourse, location as well as analysis of creators and their institutions.

Background

College media are growing into an active area of scholarly research as campus-based media outlets provide a training ground for student practitioners (Wotanis 2016; Chappell 2015; Kolodzy et al. 2014; Sarachan 2011; Huang et al. 2006). Despite this growth, college magazines remain understudied. On a college campus, a magazine records a moment in time; as documenters of life for a defined community, staff editorial decisions reflect campus culture as much as the editor-in-chief at that moment.

Recent data indicate the campus magazine is stable (Benchmark Survey, Kopenhaver 2022): media advisers advise these publications at least annually (46%), on par with 2015, which showed growth in publication frequency and page count. Additionally, web versions not only mirror some print content, but offer routine and frequent updates, thus, adding fresh content (Kopenhaver, Smith, and Biehl 2021).

Prior literature confirms the magazine medium as a unique cultural form (Piepmeier 2008). Magazines – consumer, trade, niche, campus ¬ – build communities of interest among the readership; the content expresses and explores a community’s culture, ideals, and identity. Thus, as cultural artifacts, (Piepmeier 2008; McQuail 2005) magazines continue to be valid for study.

Literature Review

Environment, Society, and Magazines

Since the medium’s heyday (1880 to 1920), magazines remain central for scholarly research (Prijatel and Johnson 2013). This timeframe creates a structure to examine content, operations, and innovations. Content themes such as nature and environment have been analyzed, especially in terms of reader uses, reaction, and satisfaction (Takahashi and Tandoc 2016; Meisner and Takahashi 2013; Labbe and Fortner 2010; Knight 2010; Neuzil 2008; Donovan and Brown 2007; Schoenfeld 1983).

While environmental movement scholars trace and often debate its history, scholars of environmental news list the late 1960s as key (Friedman 2015), spurred in part by publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962). With science an addition to the discourse, readers increased interest in their ambient environment.

Also at this time, activism surges following a Santa Barbara oil spill: Sen. Gaylord Nelson proposes creation of Earth Day amid protests over fossil fuel reliance. What follows is a busy legislative period: establishment of the EPA and ESA, Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, and more.

Prior to this legislation whirlwind of 1968 to 1972, magazines covered environment more frequently than mainstream publications (Knight 2010; Neuzil and Kovarik 1996). A spike in mainstream media coverage occurred post-agency creation, suggesting, “environmental issues were initiated not by the general interest media, but by professional interest groups, specialized [magazine] publications, and the government bureaucracy” (xix). But, compared to other media, magazines remain understudied in the environmental communication arena, some suggest, because of an editorial impact and role in reflecting and shaping community discourse (Meisner and Takahashi 2013; McQuail 2005).

Environmental communication research confirms a prevailing theme that positions the environment as an economic resource as opposed to a public benefit or civil right (Terracina-Hartman 2019; Knight 2010, Allan, Adam and Carter 2000). In the early 2010s, research on climate change communication confirmed these discussions were best framed in pragmatic terms, such as public health, disease transmission, crop impacts, severe weather occurrences, cost-saving measures, and more (Myers, Nisbet, Maibach, and Leiserowitz 2012; Maibach et al. 2010).

With social media campaigns aimed at college-aged audiences in early 2010s (e.g., Sierra Club’s 2011 Beyond Coal and ‘Unfriend Coal’) and the activism of Greta Thunberg and her Sunrise Movement in the late 2010s, this dialogue shifted and moved (Lovejoy and Saxton 2012; Lovejoy, Waters, and Saxton 2012; Keniry 2010). Lack of action – amid dire warnings from IPCC reports – motivated Gen Z to stand up and demand their future, in a sense, decrying lack of action as dangerous as inaction on gun safety. Social media usage among nonprofit environmental groups targeted this population with dialogic opportunities and landed: three purposes are identifiable (Lovejoy and Saxton 2012) information, community, and action. Early scholars in environmental communication noted the movement aligned a clean environment with civil rights; in this digital arena, climate actors advocate for policy change, political action, and most importantly the social justice issues involved in climate change (Chen et al. 2023; Weinstein et al. 2015). Tracking climate change discourse 2018–2021, researchers found several themes of predominance, including, “policy discussion: climate justice.” Keywords included communities, social, recovery, vulnerable, women, solve, populations, native, learning, action, effective (Chen et al. 2023, 401). These themes peaked as the U.S. headed into COVID-19 pandemic shutdown. Brown and Hawlow (2019) noted how protest (or ‘climate strike’) coverage appeared to delegitimize marginalized communities while Ludwig (2020) documented a discourse shift in which debate moved from science to individual responsibility to policy and community efforts; however, the COVID-19 shutdown and hyper-focus on individual actions appear to have altered that emphasis (Haßler, Wurst, Jungblut, and Schlosser 2023). Thus, the discourse has shifted in which Gen Z talking about climate change is tangible in ways that was not tangible to Baby Boomers two decades ago (Tyson, Kennedy, and Funk 2021; Keniry 2010).

Gen Z engaging more with climate change content is visible in at least four activities listed during a recent Pew survey (2021): donating, contacting elected official, volunteering, attending rallies and protests. This engagement appears to parallel activism ignited during the 2018 culture wars, after the Parkland shooting, and on college campuses (della Volpe 2022; Tyson, Kennedy, and Funk 2021; Keniry 2010). Results show Gen Z and millennials are more active than older generations addressing climate change on and offline (55). Additionally, surveying for five conditions (excess of garbage, water pollution, local air pollution, lack of greenspace, no safe drinking water), Pew researchers report 60% of respondents indicated they see “moderate” environmental problems where they live (Tyson, Kennedy, and Funk 2021, 56).

Theoretical Background

It is appropriate to reference Stuart Hall and grounded theory in discourse analysis of media texts. Early on, Hall writes the form of the message “has a privileged position in the communication exchange and that the moments of encoding and decoding though only relatively autonomous in relation to the communicative process as a whole, are determinate amounts” (1973, 2).

Hall agrees that repetition is key to discourse analysis – whether it be visual (headline, photo, page design) – or change in style or production, as it can signify importance as well as unimportance. Like Gerbner, however, scholars agree any change in media production may be most worthy of study: “What stands out as unusual or exceptional may have the greatest weight” (Steiner 2016, 104).

Two threads of research converge in Hall’s model: the processes leading to content production and the other, which views media as symbolic artifacts, essentially arbiters of routine. Alongside this effort is belief among early magazine scholars, who argue for balancing content between ‘giving readers what they ought to read as well as what they want to read’ (Ray Cave, quoted in Johnson and Prijatel 2013): and “What matters most is not what the editor puts into a publication but what the reader takes away” (Johnson and Prijatel 2013, 249). Likewise, Hall argues that newspaper producers declare they are giving their audiences what they seek; however, it’s not clear whether the readers know what they want or don’t want (1975).

Hall emphasizes that “dominant” meanings are not “majority” meanings; thus, he argues that media producers may favor or present specific encoding, but are unable to control meanings for receivers. And while he rejects the notion of hypodermic-needle theory of media effects, he acknowledges the power with which media producers can create and establish cultural structures by which groups and their members tend to operate.

The concept of meaning wanders into framing theory. A frame continues to offer a context-specific structure by which to examine meaning-making; framing theory offers an additional avenue to examine these choices and usage over time. Gerbner et al. (2001) suggest this repetition in mass media – essentially construction of a “frame” – leads to cultivation not only in meaning, but likely also in attitude among producers and receivers.

Four approaches exist by which to assess frames in media content (Entman, Mathes, and Pellicano 2009). A qualitative approach aims to identify frames by tracing usage in discourse of a single event over time (see e.g., Esser and D’Angelo 2003; Pan and Kosicki 1993). A frame can be “identified by analyzing selection, placement, and structure of specific words and sentences in a text” (2009, 180) with researchers setting parameters for analysis (Pan and Kosicki 1993).

Dunwoody (1992) defines a media frame as a, “knowledge structure that is activated by some stimulus and is then employed by a journalist throughout story construction” (p. 75). Recent research into college media content finds campus newspapers lead with campus news (47%), student life (15%), followed by sports (9%). Of the hard news that were lead stories, 26% were tied to a national, news issue, yet 87% related to a campus issue (Lyon Payne and Mills 2015). For the purposes of this study, frame is assessed by geophysical or perceived location identified in the article (Adams and Gynnild 2013).

Semiotics also is appropriate for this analysis as together they capture denotation – specific, literal, precise meanings – and connotation – historical, sociological, psychological, and highly individual meanings.

In line with prior research, it was the intent to examine college magazine content and allow categories to emerge from the data, thus gathering representations over time (Foss 2005; Glaser 1992; Strauss and Corbin 1990). From there, key words define themes, signaling a “commonsense meaning” of how student journalists construct messages of environment and Nature in their campus lifestyle magazines.

Research Questions / Hypotheses

This study uses semiotic analysis to examine environmental communication in a content analysis of campus magazines 2018–2022.

This study offers three research questions:

RQ1: How prominent are environment themes in campus magazine content 2018–2022?

RQ2: Are trends visible in where these themes appear?

RQ3: How is location used to frame commonsense meanings of ‘environment’?

Building on prior work (Terracina-Hartman 2019; Knight 2010; Podeschi 2007) the study gauges theme frequency, records locations, type of institution, and develops key words (e.g., accountable, narrative, intention) to record discourse occurrences.

Based on prior work (Seelig and Deng 2022) of messaging findings and climate change anxiety and activism (Weinstein 2015; Terracina-Hartman, Bienkowski, Myers and Kanthawala, 2014; Adams and Gynnild 2013; Keniry 2010) among college-aged populations, the following hypothesis is offered:

H1: Creators issue personal and communal “call to action” in environmental content.

Methods

To contribute to knowledge of campus media operations, this study selected award-winning (placing 1st, 2nd, or 3rd) campus magazines from three national college media competitions: Associated Collegiate Press Pacemakers, College Media Association Pinnacles, and Columbia Scholastic Press Association Crown, collecting content from editions published 2018 through 2022.

Honorable Mentions were discarded as awarding was not uniform. Literary magazines and magazines not 100% student-run were filtered out and discarded. This yielded a sample N = 55 publications (Appendix 1).

A codebook was adapted from prior study of college magazines (Terracina-Hartman 2024) while an environmental news code was adapted from Knight (2010) framing study of news and magazines (Appendix 2). A coding team trained on editions not in the dataset to refine the identified themes, subtopics, locations, type of institution, and department. With Scott’s pi value of .84, the team established demonstrated intercoder reliability on 5 variables (and others not in this study: graphical treatment and length).

Using central tenets of fundamental semiotic principles (see e.g., Barthe 1972; de Saussure 1959) content was reviewed to reveal prominent themes, or meanings: 10 themes were identified organically, with minor trends tied to each theme to include variabilities (e.g., climate change and global warming). Content pertaining to prominent environmental themes were then selected for analysis, with measurement also for occurrences of #COP26, #SavethePlanet, #DitchtheBottle, #2020 hashtags prominent during the study period.

List of prominent themes:

- solutions

- sustainability

- conservation

- policy: corporate polluters, fossil fuels, individual

- fashion / art / beauty

- activism / accountability / responsibility / minimalism / 2020

- food: production / systems

- hazard / crisis (wildfire, drought, flooding), extreme weather

- pollution

- human-caused climate change

Results

Of the 215 eligible elements from 55 award-winning publications, N = 114 eco- and Nature-related themes for analysis. After a review of data and open-ended responses using key words (e.g., global warming), yielded N = 135 elements for analysis.

A review of results confirms Seelig and Deng (2022) and Weinstein et al. (2015) in terms of discourse trends: prevention rather than mitigation; act don’t react. Discourse analysis reveals discussion of a range of social issues, presenting environmental themes as a measure of civil rights, a matter of personal responsibility, and – at the dawn of a new decade – a moment for this generation to be active, positive, pro-active, and beyond approaches and / or politics of prior generations.

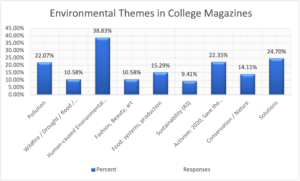

To answer RQ1, a frequency analysis shows most commonly occurring themes were Human-Caused Environmental Impacts / Climate Change and Activism (Fig. 1).

The most prominent categories are Climate Change (33, 39%), Solutions (21, 25%) and Activism (19, 22%). And while Fashion / Beauty / Art occurs 11%, its environmental frame indicates an overall news value as discourse features responsible fashion choices, sustainable design, fair trade textile and cosmetic suppliers, as well as entrepreneur creators doing all these things. Readers are asked to consider the environmental impact of their choices in clothing, cosmetics, and creating. Ball Bearings spring 2021 edition ‘Woven Identities’ theme features “The Ethics of Thrifting” (12, edition 2) details how shoppers choose to frequent consignment or used clothing stores to avoid ‘fast fashion’ and reduce the industry’s impact on climate change by reducing amount of clothing sent to landfills. On the fall 2019 cover: “The Cost of Curls” and “The Truth About Climate Change” (vol 11, edition 1), while inside readers find a feature on climate change activist Kate Elder, who chooses hope and change as she protests alongside others. Similarly, The Collegian Times uses a Game of Thrones-like image to introduce its history-themed Spring 2022 edition. Teasers promise readers a deep dive into La Brea Tar Pits to learn if dire wolves once walked LA the last Ice Age and how climate change + humans drive species to extinction.

Pollution (19, 22%) closely follows Activism, but surprisingly, drought / severe weather content (includes hurricane, heat wave, deep freeze, etc) is low; writers’ content references air and water pollution from factories, DOE sites, pesticide usage, automobile exhaust, single-use plastics, and more. Again, the discourse emphasizes steps readers can – and should – take to reduce the impact of their lives on their homes, communities, their campus, and their future with solutions-themed content (21, 25%).

As a general practice, the Editor in Chief pens their column as the edition is about to be published, thus allowing the possible inclusion of timely updates and information. That also allows for unique content – introduction of issues or the publication’s stance – that might not appear elsewhere.

A review of literature indicates editors’ voices – whether individual or collective – draw a wide audience and carries much importance. To the objection the editor’s job is to “give news, not views,” (Dumont, 1919, 6) a dismissal was provided as early as 1912: “From [their] position, the editor is morally obliged to give comment. [They are] the one [person] in the community, usually, who has the greatest number of avenues to knowledge of current events; [they are] in a position to know more about the trend of affairs both local and foreign than anyone in the community” (1919, 6).

Acting as the voice for a campus community, campus magazine editors 2018–2022 wrote about climate change and area pollution, issuing generational calls to action and local activism on these issues (41%). Trending deeper into threats facing the community, additional discourse addressed wildfire’s impacts on public health, air and water quality, and the impending – perhaps inevitable – mudslides during the rainy season. Editors called on their community to choose sustainability (55, 78%), such as create defensible space, be active with tree planting programs, avoid single-use plastics, shop in bulk, choose alternate transit (public, skateboard), and compost food waste. Also, most specific: activate campus clubs to advocate for campus sustainability programs to expand recycling, use fair trade vendors, choose biofuel sources, and other options to be a model for the surrounding community. Unlike other sections, these columns emphasized “#choosethisfight” alongside #ourfuture” and #brightertomorrow that do not appear in other sections. This content coincided with #2020 and #choosetosavetheplanet campaigns common on college campuses as a new decade dawned alongside the activism of Greta Thunberg and the Sunrise Movement. Writes one editor in Spring 2020, “Thunberg along with the Australians [staff writers], have reminded me that with each decade comes something to fight for – why not make 2020 a fight for our planet …?” (Vaccaro, 7). While another Editors’ Letter highlights content detailing groups advancing outdoor equity in spring 2021 (Echo, 2021, 7), another introduces a light / dark edition theme, describing how humans lighting up their world threatens species who live in the dark: “The point of this magazine is to challenge a culture in which elements such as dark and light are polarized and pitted against each other” (Lolacano, 2019, 4).

With a content theme of food: production / systems, results show editors used their columns to highlight family and community traditions presented in edition content (48%). As the pandemic shutdown appeared in their columns, such highlights spotlight the community with profiles of everyday heroes. We find this theme in Ball Bearings spring 2022 “The Muncie Issue,” which spotlights local groups studying farmers and food distribution systems to get food to the community, targeting individual neighborhoods; we see family generations, their culinary traditions, and how this leads one woman to entrepreneurship; and a discussion of outdoor safety for all. Elements of sunscreen damage to marine life and our endocrine systems: one writer breaks it all down and tells readers where to read ‘Reef Safe’ labels and how. Editors point to this content with pride, stating their intention and attention to the reading community.

With a dominant expression of Solutions (59, 85%) – tips for taking action at “home” (campus, community), profiles on “community heroes,” such as a firefighter / student / mother – the co-occurrence of environment content with Solutions using a Community frame (27, 32%) confirms an editorial approach and voice to this column over time and across publications.

H1 states “creators issue personal and communal call to action in environmental content.” A total review of content featuring a call to action invoking a ‘community’ voice, with keywords such as “we must,” “together,” “us,” “let’s,” “for our future,” and more in content themes of fashion or food choice accountability, community activism for prevention, or conservation of habitat or Nature spaces, accounts for 88 occurrences or 68%, of content across 2018–2022.

Thus, H1 is supported.

To answer RQ2, a frequency analysis was conducted across all identifiable sections, with three standing sections selected for further analysis, in line with prior literature (Terracina-Hartman, 2024): Editor’s Note, Cover, and Table of Contents. Approaches vary to these standing elements; therefore, analysis over time is valid.

Results show Environmental and Nature-theme content prominent in Editors’ Note (30, 43%) and Cover Art (45, 64%). Table of Contents, which ranged from a single page and 1 photo behind a bulleted list of content to 3 pages with an array of photos, graphical text treatment, and a specialized banner also appeared prominent, with 43, (61%) in the results.

The Table of Contents section can serve as “a second front page” for editors to graphically highlight content. These choices are worthy of study as often, a Nature or environmental-themed story carries much opportunity and demands many design decisions: severe weather, loss, cleanup, recyclables, collections, heroes / helpers, entrepreneurs, and more. Content that features severe weather conditions follows an issue-attention news cycle (Downs 2016), but in a magazine, the content cycle must follow the story of the community; thus, beginning with social impacts of events, such as loss and survival and how this very big story looks and continues to look in the community. Capturing those voices with images and graphics is essential to guide the reader through to the content. When a community experiences change, juxtaposing a historical photo alongside a current photo can tell a story even before readers consume any text. While research definitively confirming the effects of photo and graphic usage on comprehension, attention, distraction, or attraction is absent, recent work confirms that such usage does elevate the level of importance for readers (Zillman, Gibson, and Sargent 1999). Additionally, for readers drawn to visual media, the possibility of selective perception may be at play (Powell, Boomgarden, De Swert, and de Vreese 2015; Zillman, Knobloch, and Yu 2001).

Turning to cover art, the approach varies: illustration vs photographs; stark design vs cover lines. Each speaks to creator voice and reading audience. Post-shutdown, images became intimate featuring heroes, helpers, and solutions. Of the 45 covers featuring environmental elements (59%), 30 used a full-page photo, (43%), 13 produced a photo illustration (29%), and 2 offered a secondary photo (4%).

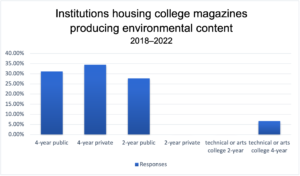

To extend this analysis, variables that may contribute to production must be considered, such as institutional and student demographics; therefore, considering the type of institution producing this content is warranted. Results show 4-year private institutions produced most content with environmental or Nature meanings (Fig. 2).

The location of these institutions may contribute to the editors’ content decisions as well as the student demographics. As magazines build communities and reflect communities (Gill and Babrow 2007) and editorial distance between editors and their reading community is less than in other news-type outlets (Abrahamson 2009), these location data offer a significant glimpse into how creators react and interact with the physical environment(s), thus creating a frame for their environmental content.

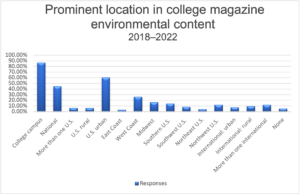

To further examine this question, RQ3 asks how location serves to frame environment and Nature-themed content. A frequency analysis counts types of locations referenced in content. The intent of this question is to examine what are the commonsense meanings of environment and Nature in the discourse among college media creators. One method for writers to create prominent meanings, or frames, is through identifiers, such as geolocations – placing readers in time and space (Adams and Gynnild 2013. Whether the writers focus the prominent meanings on campus, the surrounding community, a region, or the planet, the content is framed much the way a person looks out of a house through a window (Entman, Mathes, and Pellicano 2009): the frame constructs a specific worldview for the reader to process meaning. Do college magazines present environment-themed content, such as a climate change concern, taking place in hyper-local frame or is the writer crafting a national concern and trying to sift the information to create location frame relevance for the reading community?

Frequency results indicate 87% frame campus location as prominent, followed by U.S. urban (60%) (Fig. 3), while 41 is a national frame (45%). For regional references, West Coast leads (24, 26%), while Midwest and Southern appear nearly equally (17%). These decisions speak to discourse consistency in creating relevant content to the reading audience, but also with a language of activism and of empowerment: climate change is an issue here there and locally and here is what we, readers, can do with our daily choices on campus, in the community, and perhaps achieve a nationwide effect, aligning with prior research (Adams and Gynnild 2013). Given the data showing dominance of activism and campaigns #choosetosavetheplanet, the discourse would be relevant to the campus reading audience (Tyson, Kennedy and Funk 2021; della Volpe 2022) and likely in the surrounding community. As noted in prior literature, the discourse focuses on community and storytelling – unlike newspapers that often lead readers toward decisionmaking on an issue, magazine content digs deep into social issues and how issues affect community; readers are asked to identify with humanity and what that issue looks like.

Writes one Editor-in-Chief in a 2022 special edition, “After observing misinformation in media and society surrounding climate change, I knew it was necessary to communicate responsibly and effectively about climate change to our audience” (Levins, 4).

Flux reframes the word “uncertainty,” linking it to a post-fire, post-protests, and mid-pandemic “Resilience” theme of the Spring 2021 edition. Writes the editor, “The world still turns and people carry on in any way they can. If anything, these times have proven how resilient we truly are” (Daehlke, 4). Framing these issues – state, national, global – with storytellers in the community “United Through Activism,” creators promote action and support: community leaders raising awareness of institutional racism and promoting community engagement; supporting protests against Asian hate and providing a safe space; studying the media for trans representation and rurality.

Lastly, Talisman introduces its fall 2021 edition’s content – which takes readers above and below Earth: spelunking and searching for their personal talisman – acknowledging its intention and goal for readers. Executive Editor Jess Brandt writes, “The Talisman has and always will attempt to reflect the spirit of WKU and the larger community through everything we do. As you read Issue No. 11, I urge you to leave these pages with a greater sense of wonder around you, searching for the moments of life that are simply human” (2021, 5).

Discussion

This study builds on prior work aiming to examine discourse and editorial operations of college magazines during recent historical moments in time. The medium of magazine has established itself as a builder and uniter of community when the community itself seeks a vehicle for doing so. The microcosm of a college campus – where the outside community and external social conditions may be visible on the pages of a lifestyle publication – offer a solid starting point for examination of discourse and content.

Results confirm Seelig and Deng (2022) in terms of prominent meanings and minor trends: action rather than mitigation. Semiotic analysis reveals discussion of a range of social issues, presenting environment themes as a measure of civil rights, a matter of personal responsibility, and – at the dawn of a new decade – a moment for the current generation to be active and reject what prior generations have created. This finding appears to be in line with current and broader research into Gen Z’s overall use of discourse, messages, and symbols (Chen et al. 2023; della Volpe 2022; Tyson, Kennedy and Funk 2021).

What’s notable is frequency in prominent meanings over time particularly as “campus life” drastically changed outside: from the culture wars in 2018 to the COVID-19 pandemic shutdown to returning to in-person learning in early 2022, the appearance of environment and Nature-themed messages appear in standard locations and standing features while commonsense meanings were revised to stay relevant to the times. We see discussions of global climate change encouraging personal responsibility to participate in a generational effort while profiles on individual heroes and activists are highlighted in Editor’s Note and Table of Contents. Cover art illustrations dominate – illustrating what might be left of Earth in the near future if we don’t embrace #2020 #choosetosavetheplanet campaigns.

We see this in the results: the Solutions theme takes a different trend in profiling heroes, family traditions, community celebrations #doingthe19. Fashion, art, beauty creators and needs are different when students spend their days on Zoom and their supplies are limited; discussions of upcycle take on a different meaning with an emphasis on #safeathome and #shortage of needed supplies take over, particularly for those who navigate chronic conditions. As a prominent meaning, Food Systems / Production discourse co-occurred with Solutions during the COVID-19 shutdown: A food shortage figured prominently during these editions; growing food, starting community gardens, forming co-ops, establishing blessing boxes and taking / leaving food appear as minor trends. This result supports the dominant meaning “be active” noted in other works.

The call to action dominates much of the editorial voice, particularly when the editor-in-chief introduces new topics. Again, the suggestion is to be active, be accountable, live with intention and responsibility. And, get outside! Enjoy Nature and here’s a list. While traditional news outlets provide the doom and gloom data of a changing climate, the magazine community focus permits this direct connection narrative: let’s protect our world. ‘Our world’ in discourse appears most prominently as campus and the urban environments. Prior research has noted that scholars tend to neglect the magazine medium as a research interest due in part to its less definable editorial impact, which reflects and shapes the discourse of its readership into a niche community (McQual 2005).

The intent of this study was to analyze five years of data; however, CSPA and CMA 2023 contest changes favor restricting data collection to four years.

Limitations and Future Research

While the study period covers years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic shutdown and the years returning to in-person learning, it’s not possible to approximate how or if the student editors or creators turned their attention more or less to environmental concerns during these historic moments without referencing the chaos of culture wars, the pandemic shutdown and all the attention to personal habits that #safeathome involved, and the activism that converged with these global, national, and regional events. What may be missing are magazines that didn’t appear in the winners’ circle of the three national college media contests because of pandemic disruption; while the CSPA, CMA, and ACP database indicate a consistency in entries / colleges over a 10-year period, it is not yet possible to review a list of entries that did not win nor colleges that were uncharacteristically absent during the pandemic shutdown years.

While a separate paper examines the content of articles in this dataset, further research should continue to explore the relationship between Gen Z’s expression of nature and environment and the prevailing frame of activism, solutions, and accountability – perhaps to further refine or update a definition. Additionally, further variables for study include use of graphics and visuals. Smith & Joffe (2009) found UK Press used visual representations of climate and environmental issues in three ways, primarily by telling people’s stories rather than scientists’ data. Magazines, similarly, personify an issue or event by illustrating the social impacts on their readership – Hurricane Michael, Camp Fire, Texas Deep Freeze, wetland loss in Louisiana, fracking wellheads in Pennsylvania. Their definitions relied on interactions with Nature (animals, places, plants, weather) and environment (places, scientists, politicians, conservationists), Similarly, Meisner and Takahashi (2013) defined environmental discourse as relationships between humans and nature: issues, players, actions (257), but this study’s dataset, as noted earlier, indicates “the environment” is in our homes and down the street at the park – integrated to daily life.

Whether these dominant meanings persist beyond these historical perhaps unprecedented times also is worthy of study. Following award-winning editions for a five-year period to survey consistency of this type of content over time rather than in editions selected for – and winning – as a content submission. Additionally, further investigating location frame and type of institution over time may reveal a consistent campus life value that existed – and persisted through the COVID-19 pandemic – or a recent news value visible in the content. A content-oriented frame analysis encompasses both generic and topical themes: generic (conceptual e.g., morality and consequence) and topical (issue-specific). The 2018–2022 time period invites further examination into college media content and production given the unprecedented social conditions in which these student creators were operating.

Scholars agree it’s not delivery that drives media effects, it’s content and repetition; thus, we need to continue to study how this repetition – and the choices leading to usage – are constructed. To approach such analyses from a different method, future research might consider multimodal discourse analysis (Kress and van Leeuwen 2001). Were a collection of each magazine’s print and digital editions available, comparing the digital and print homepages for content as well as tracing the environmental content outside of the top three departments in which such content appears in this study (digital vs. print) could provide valuable insights into discourse, visual values, and content framing over time.

Lastly, comparing Editor’s Note content with news content by theme is a worthwhile topic for study; the data might reveal additional insight into discourse patterns and issue framing for publications over time.

References

- Abrahamson, D. (2009). The future of magazines 2010–2020. Journal of Magazine and New Media Research 16(1), 1–3.

- Adams, P. C., and Gynnild, A. (2013). Environmental Messages in Online Media: The Role of Place. Environmental Communication, 7(1), 113–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2012.754777

- Allan, S., Adam, B., and Carter, C. (2000). Introduction: The media politics of environmental risk. In S. Allan, B. Adam, and C. Carter (Eds.), Environmental risks and the mass media (pp. 1–25). London, UK: Routledge.

- Altheide D. L., and Schneider C. J. (2013). Qualitative media analysis (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Ball Bearings. (2022). The Muncie Edition. Vol. 11, No. 2.

- Bateson, G. (1954 / 1972). A Theory of Play and Fantasy. In Steps to an Ecology of Mind. Ballantine Books: London, UK. (175–190).

- Boykoff, M., and Luedecke, G. (2017). Environment and the Media. In D. Richardson, N. Castree, M.F. Goodchild, A. Kobayashi, W. Liu, and R.A. Marston (Eds.). The International Encyclopedia of Geography. John Wiley & Sons: London, UK. DOI: 10.1002/9781118786352.wbieg0464

- Brandt, J. (2021). Editor’s Letter. The Talisman. p. 5.

- Brosius, H.B. and Eps, P. (1995). Prototyping through Key Events: News Selection in the Case of Violence against Aliens and Asylum Seekers in Germany. 10(3), 391–412.

https://doi.org/10.1177/026732319501000300 - Brown, D. K., & Harlow, S. (2019). Protests, media coverage, and a hierarchy of social struggle. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 24(4), 508–530.

- Chappell, S. (2014). Convergence Can Work … It Just Might Take Three Years. College Media Review. 54, 12–28. cmreview.org/convergence-can-work/.

- Charmaz, K., and Henwood, K. (2017). Grounded theory methods for qualitative psychology. The SAGE handbook of qualitative research in psychology, 2, 238–256.

- Chen, K., Molder, A.L., Duan, Z., Boulianne, S., Eckart, C., Prince Mallari, P., and Yang, D. (2023). How Climate Movement Actors and News Media Frame Climate Change and Strike: Evidence from Analyzing Twitter and News Media Discourse from 2018 to 2021. The International Journal of Press/Politics. 28(2), 384–413.

- CMA Benchmarking Survey (2022). College Media Association.

http://cma.cloverpad.org/resources/Documents/2022BenchmarkingSurvey22Results.pdf - CMA Benchmarking Survey (2020). College Media Association. http://cma.cloverpad.org/resources/Documents/2020BenchmarkingSurvey20Results.pdf

- Davidson, D. J., Rollins, C., Lefsrud, L., Anders, S., and Hamman, A. (2019). Just don’t call it climate change: climate-skeptic farmer adoption of climate-mitigation policies. Environ. Res. Lett. 14 034015 DOI 10.1088/1748-9326/aafa30

- Daehlke, S. (2021). Editor’s Note. Flux ‘Resilience’ Edition. Issue 28, p. 4.

- della Volpe, J. (2022). Introduction. Fight. (pp. 1–8). New York: St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

- Donovan, G. H. and Brown, T. C. (2007). Be careful what you wish for: The legacy of Smokey Bear. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 5, 73–79. doi.org/10.1890/1540-9295 (2007)5[73:BCWYWF]2.0.CO;2

- Downs, A. (2016). Up and down with ecology: The “issue-attention cycle.” In Agenda setting (pp. 27-33). New York: Routledge.

- Dumont, W. P. (1919). The Editorial Field: A Collection of Expressions with Regard to the Editorial Function, Opportunity, Responsibility, Method and Style of Writing. 1(3): 2–19. The Ohio State University Bulletin: Columbus, Ohio.

- Dunwoody, S. (1992). The media and public perceptions of risk: How journalists frame risk stories. In The social response to environmental risk: Policy formulation in an age of uncertainty (pp. 75-100). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Editors’ Letter. (2021). Echo magazine. p. 7

Entman, R. M., Matthes, J., and Pellicano, L. (2009). Nature, sources, and effects of news framing. The handbook of journalism studies, 175–190. - Esser, F., and D’Angelo, P. (2003). Framing the press and the publicity process: A content analysis of metacoverage in campaign 2000 network news. American Behavioral Scientist, 46, 617–641.

- Foss, S. K. (2005). Theory of visual rhetoric. Handbook of visual communication: Theory, methods, and media, (pp. 141–152). New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Friedman, S. M. (2015). The changing face of environmental journalism in the United States. In The Routledge handbook of environment and communication (pp. 164–226). Routledge.

- Gerbner, G., Gross, L., Morgan, M., and Signorielli, N., and Shanahan, J. (2001). Growing Up With Television: Cultivation Processes. In Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research (2nd ed). J. Bryant and D. Zillmann (Eds.) Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. In press.

- Gill, E.A., and Babrow, A.S. (2007). To Hope or to Know: Coping with Uncertainty and Ambivalence in Women’s Breast Cancer Articles. Journal of Applied Communication Research 35(2), 133–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909880701263029

- Glaser, B. (1992). Basics of Grounded Theory Analysis. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

- Goffman, E. (1974/1986 ed.). Frame analysis: an essay on the organization of experience. Boston, Mass.: Northeastern University Press.

- Guggenheim, L., Jang, S. Mo, Bae, S. Y., Neuman, W. R. (2015). The Dynamics of Issue Frame Competition in Traditional and Social Media. ANNALS, AAPSS, 659. doi: 10.1177/0002716215570549.

- Haßler, J., Wurst, A. K., Jungblut, M., & Schlosser, K. (2023). Influence of the pandemic lockdown on Fridays for Future’s hashtag activism. New Media & Society, 25(8), 1991–2013.

- Hall, S. (1973). Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse. Paper for the Council of Europe Colloquy on “Training in the Critical Reading of Televisual Language.” Council & the Centre for Mass Communication Research, University of Leicester.

- Hall, S. (1975). Introduction. In A. C. H. Smith, E. Immirizi, and T. Blackwell (Eds.), Paper voices: The popular press and social change 1935–1965. London, England: Chatto and Windus.

- Hall, S. (1980a). Encoding/decoding. In S. Hall, D. Hobson, A. Lowe, and P. Willis (Eds), Culture, media, language (pp. 128–138). London, England: Hutchinson.

- Hall, S. (1980b). Introduction to media studies at the Centre. In S. Hall, D. Hobson, A. Lowe, and P. Willis (Eds.), Culture, media, language (pp. 117–121). London, England: Hutchinson.

- Huang, E., Davison, K., Shreve, S., Davis, T., Bettendorf, E., and Anita, N. (2006). Bridging Newsrooms and Classrooms: Preparing the Next Generation of Journalists for Converged Media. Journalism and Communication Monographs 8(3), 221–262.

- Johnson, S., and Prijatel, P. (2013). The magazine from cover to cover. 3rd ed. London: Oxford University Press.

- Johnson, S. (2007). Why should they care? The relationship of academic scholarship to the magazine industry. Journalism Studies, 8(4), 522–528.

- Keniry, J. (2010). Environmental Movement Booming on Campuses. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 25(5): 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.1993.9939904

- Kolodzy, J. E., Grant, A. E., DeMars, T. R., and Jeffrey S. Wilkinson, J. S. (2014). The Convergence Years. Journalism and Mass Communication Educator. 69(2), 197–205. doi: 10.1177/1077695814531718.

- Kopenhaver, L.L. 2022 Benchmark Study. available URL: collegemedia.org Accessed 10/1/2023

- Kopenhaver, L. L., Smith, E., and Biehl, J. K. (2021). The College Newsroom amid COVID. College Media Review 58(1), 38–55.

- Kopenhaver, L. L. (2015). Campus media reflect changing information landscape amid strong efforts to serve their communities. College Media Review, 52(1), 38–55.

- Knight, J. E. (2010). Building an environmental agenda: A content and frame analysis of news about the environment in the United States, 1890 to 1960. Ohio University.

- Kress, G. and van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal Discourse: The Modes and media of Contemporary Communication. London: Arnold.

- Labbe, C. P., and Fortner, R. W. (2010). Perceptions of the Concerned Reader: An Analysis of the Subscribers of E/The Environmental Magazine. Journal of Environmental Education 32 (3), 41–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958960109599145

- Levins, A. (2022). Letter from the Editor. The Graphic: Special Edition, 4.

- Lippmann, W. (1922). Public opinion. New York: Free Press.

- Lolacano, M. (2019). Letter from the Editor. Currents. 113, 4.

- Lyon Payne, L., and Mills, T. (2015). What’s in the Pages?: A Current Look at College Newspaper Content from Various Collegiate Environments. College Media Review, 52(1), 15-27.

- Maibach, E. W., Nisbet, M., Baldwin, P., Akerlof, K., and Diao, G. (2010). Reframing climate change as a public health issue: an exploratory study of public reactions. BMC public health, 10(1), 1–11.

- McQuail, D. (2005). McQuail’s mass communication theory (5th ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage

Publications. - Meisner, M. R., and Takahashi, B. (2013). The nature of Time: How the covers of the world’s most widely read news magazine visualize environmental affairs. Environmental Communication, 7(255), 255–276. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2013.772908

- Mudra, I. (2015). Editorial column as self-promotion for publishers. In Litteris et Artibus. Lviv Polytechnic Publishing House 424–425.

Myers, T. A., Nisbet, M. C., Maibach, E. W., and Leiserowitz, A. A. (2012). A public health frame arouses hopeful emotions about climate change: a letter. Climatic change, 113, 1105–1112. - Neuzil, M. (2008). The Nature of Media Coverage. Forest History Today. 4, 32–39.

- Nierenberg, A. (2020). Covid Is the Big Story on Campus. College Reporters Have the Scoop. The New York Times. www.nytimes.com/2020/11/04/us/college-journalists-covid.html.

- Nisbet, M. C. (2016). The ethics of framing science. In Communicating Biological Sciences (pp. 51-74). New York: Routledge.

- Orsini, M. M. (2017). Frame Analysis of Drug Narratives in Network News Coverage. Contemporary Drug Problems, 44(3): 189– 211. doi.org/10.1177/0091450917722817

- Pan, Z., and Kosicki, G. M. (1993). Framing analysis: An approach to news discourse. Political Communication, 10, 55–76.

- Piepmeier, A. (2008). Why Zines Matter: Materiality and the Creation of Embodied Community. American Periodicals, 18(2), 213–238.

- Podeschi, C. W. (2007). The Culture of Nature and Rise of the Modern Environmentalism: The View Through General Interest Magazines. Sociological Spectrum, 27, 299–331.

- Powell, T. E., Boomgaarden, H. G., De Swert, K., and de Vreese, C. H. (2015). A clearer picture: The contribution of visuals and text to framing effects. Journal of communication, 65(6), 997–1017.

- Sarachan, J. (2011). The Path Already Taken: Technological and Pedagogical Practices in Convergence Education. Journalism and Mass Communication Educator, 66(2), 160–174.

- Scheufele, B. (2006). Frames, schemata, and news reporting. The European Journal of Communication Research, 31(1), 65–83.

- Schoenfeld, A. C. (1983). The environmental movement as reflected in the American magazine. Journalism Quarterly, 60(3), 470–475.

- Seelig, M., and Deng, H. (2022). Connected, but are they engaged? Exploring young adults’ willingness to engage online and off-line. First Monday, 27(3). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v27i3.11688

- Sloan, W. D., and Parcell, L. M. (Eds.). (2014). American journalism: History, principles, practices. Boston: McFarland.

- Smith, N. W., and Joffe, H. (2009). Climate change in the British press: The role of the visual. Journal of Risk Research, 12(5), 647–663.

- Steiner, L. (2016). Wrestling with the Angels: Stuart Hall’s Theory and Method. Howard Journal of Communications, 27(2), 102–111, DOI: 10.1080/10646175.2016.1148649

- Strauss, A., and Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of Qualitative Research: The utility of a Wittgenstein framework. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research 3(3): Art. 20.

- Takahashi, B., and Tandoc Jr., E. C. (2016). Media sources, credibility, and perceptions of science: Learning about how people learn about science. Public Understanding of Science, 25(6), 674–690.

- Terracina-Hartman, C. (2024). “Evolution in Campus Media: How a pandemic and social justice movement prompted student journalists to rethink the campus magazine.” Journal of Magazine Media, 24 (1).

- Terracina-Hartman, C. (2019). Fanning the flames: How US newspapers framed 10 historically significant US wildfires. Newspaper Research Journal, 41(3), 368–386.

- Terracina-Hartman, C., Bienkowski, B., Myers, M., and Kanthawala, S. (2014). Social Media for Environmental Action: What Prompts Intent toward Engagement and Activism.” Technology, Knowledge and Society 9(4), 143–161.

- Tyson, A., Kennedy, B., and Funk, C. (2021). Gen Z, Millennials Stand Out for Climate Change Activism, Social Media Engagement with Issue. Pew Research Center. Accessed 1/18/2024. pewresearchcenter.org

- Vaccaro, I. (2020). Letter from the Editor. Distraction. Spring 2020, p. 7.

- Weinstein, N., Rogerson, M., Moreton, J., Balmford, A., and Bradbury, R. B. (2015). Conserving nature out of fear or knowledge? Using threatening versus connecting messages to generate support for environmental causes. Journal for Nature Conservation, 26, 49–55.

- Wotanis, L, Richardson, J., and Zhong, B. (2016). Convergence on campus. A study of campus media organizations’ convergence practices. College Media Review, 54(1), 32–45.

- Yale Law Journal. (1970). Twenty Years ‘With the Editors’. The Yale Law Journal. 79(6): 1198–1204. https://doi.org/10.2307/795261

- Zillmann, D., Gibson, R., and Sargent, S.L. (1999). Effects of photographs in news-magazine reports on issue perception. Media Psychology, 1, 207–229.

- Zillmann, D., Knoblock, S., and Yu, H. (2001). Effects of photographs on the selective reading of news reports. Media Psychology, 3, 301–324.

Appendix 1

List of Magazines

- El Sol

- Owl Magazine

- The Summit

- Baked

- Echo (Columbia College)

- Drake (Iowa)

- The Vista (Greenville University)

- Collegian (PA)

- Pacific Rim Magazine

- The Sentinel, North Idaho College

- The Bleed (2-year) (Pa)

- Ball Bearings (C)

- SHEI Magazine

- Common Ground — The Shorthorn Culture Edition

- KRNL, University of Kentucky (C)

- The Bull Magazine, Los Angeles Pierce College

- PRM, Langara College

- The Current, Amarillo College

- Distraction Magazine (Miami)

- DAMchic, (P) Oregon State U

- FORM Magazine, Duke

- MPJ / (Syracuse)

- Tusk

- Pursuit, Cal Baptist

- Ampersand (CSPA)

- Ball Bearings (C)

- Collegian Times, Los Angeles City College (C)

- Countenance, East Carolina University (C)

- Crimson Quarterly, University of Oklahoma (C)

- Dollars & Sense, Baruch College (C)

- Etc. (2-year) (C)

- Envision (Pa)

- El Espejo (Pa)

- Focus (C)

- Flux (C)

- FM/AM (C)

- Measure, Marist College (C)

- OR University of Oregon (C)

- The Point (Biola College) (Pa)

- SCAN, Savannah College of Design – Atlanta (C)

- The Stephens Life (Pa)

- Talisman, Western Kentucky University

- Tempo (Pa)

- TWO (Pa)

- Uhuru (Pa)

- Warrior Life (El Camino) (C)

- Windhover, NC State, Raleigh, NC (C)

- Woodcrest

- Blush, FIT

- Manhappenin’ K State

- Square 95

- DIG Mag (Cal State Long Beach)

- Textura

- UNF Spinnaker

- Inside Fullerton (Fullerton City College)

- City Scene (San Diego City College)

• Note: Pacific Rim Magazines becomes PRM during the study time period

Appendix 2

Coding Protocol and key words

Prominent Themes

Measures: publication, contest, theme, graphical elements, department, length, institution, location, and subtopic

I. Origin: Identify publication

II. Identify contest and year

III. Indicate themes present in content

IV. Initial themes revealed from review of content: mark visible in content

-

- pollution

- drought

- human-caused environmental impacts / climate change

- food systems production / systems / buy local

- solutions

- resources

- sustainability

- conservation

- policy

- fashion / art / beauty

- activism

- hazard / crisis weather

Theme Trends Indicated by Key Words: Mark visible in content

-

- Natural resources

- Animals / wildlife (welfare, rescue, habitat)

- Profile, community

- Explore Nature; be active

- Minimalism: create self-ecosystem

- Accountability / responsibility / inclusive

- #COP26

- #ditchthebottle

- #2020Reduce, reuse, recycle.

V. Indicate where this content is found in publication

VI. Indicate length of content (columns, pages)

VII. Presentation: Mark design elements and graphics usage

VIII. Indicate type of institution

IX. Indicate locations references in content

X. Indicate locations references in content

Carol Terracina-Hartman, Ph.D., lives in two worlds: journalism and academia. In her 20 years as an environmental journalist, she has written, edited and produced for public radio, newspapers, magazines, and digital news. A multi award-winning journalist, researcher, and media adviser, she received the Louis E. Ingelhart First Amendment Award in 2023 and Distinguished Newspaper Adviser Award in 2018 from College Media Association. She has served as Faculty Media Advisor for 17 years in 5 states. She earned a doctorate in Media and Information Studies from Michigan State University, working as a research assistant in the Knight Center for Environmental Journalism.

Carol Terracina-Hartman, Ph.D., lives in two worlds: journalism and academia. In her 20 years as an environmental journalist, she has written, edited and produced for public radio, newspapers, magazines, and digital news. A multi award-winning journalist, researcher, and media adviser, she received the Louis E. Ingelhart First Amendment Award in 2023 and Distinguished Newspaper Adviser Award in 2018 from College Media Association. She has served as Faculty Media Advisor for 17 years in 5 states. She earned a doctorate in Media and Information Studies from Michigan State University, working as a research assistant in the Knight Center for Environmental Journalism.