On educating non-journalism students, colleagues, and administrators about 1A, the role of the campus press and media advisers

By Lindsey Wotanis, Ph.D.

Marywood University

Cheryl Reed, former adviser of The North Wind, the student newspaper at North Michigan University, is the latest casualty in war between College Administrations and the First Amendment. Just a few months earlier, it was Jim Compton, former adviser of The Calumet at Muscatine Community College in Iowa.

At a time when colleges and universities around the country are facing enrollment crises, student newspapers that publish less-than-favorable stories about their campuses are seen by administrators as ‘problems’ that need handling. So are their advisers, who are often also faculty members. Sadly, the solutions to the problems are usually censorship or termination of the media advisers.

Reports have suggested that at Northern Michigan, Reed and the student in line for the editor-in-chief position were fired after the student newspaper published reports critical of the administration and of the university’s finances. Reed has since filed suit against the newspaper’s board of directors. The suit names five students and Steve Neiheisel, the university’s vice president for enrollment management and student services, whom Reed claims influenced the students to terminate her.

“Colleges and universities need to foster an open environment where student media outlets are free from interference, even from publication boards,” said College Media Association (CMA) President Rachele Kanigel in an email to members about the case. “There are many ways to bully student media and removing an adviser is simply that: bullying.”

Dana Neuts, president of the Society for Professional Journalists, told The Chronicle of Higher Education that “colleges and universities that are fortunate enough to have student newspapers should give advisers the freedom to teach students about good, ethical journalism without fear of retribution if something less than positive is published about the institution.”

But should is an operative word in that statement. Anyone who has ever advised a campus media organization knows the feeling that occurs just after a controversial story is published or aired. Often, the question that begins running through an adviser’s head is when, not if, their phone will ring.

In five years of advising Marywood University’s student newspaper, The Wood Word, I’d never once received a phone call asking me to “rethink” something that my students had published. Despite everything I had been warned about when I arrived, I’d come to believe that my fears of censorship were unfounded and that the administration at this private, Catholic institution truly was not only tolerant, but also respectful of the student press.

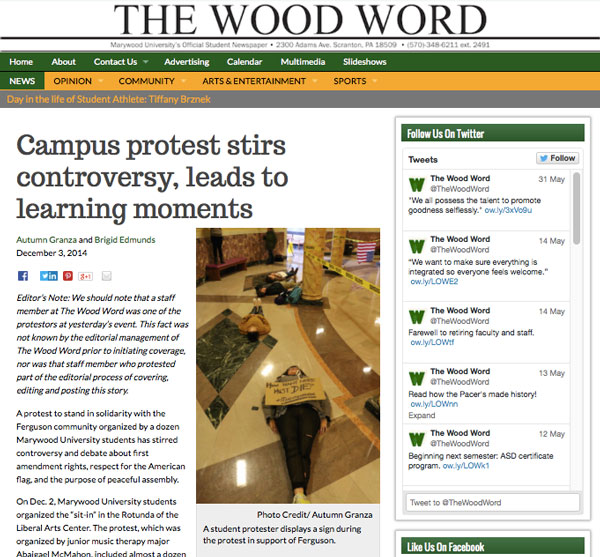

But then one of my student journalists posted a photograph of a student protester lying in one of our main campus buildings next to a United States’ flag they had hung upside and upon which was written: “There is no justice on stolen land,” the name Michael Brown, and #BlackLivesMatter.

I got the call the next day.

And though I didn’t lose my job, this story is one that is probably all too familiar to campus media advisers around the country.

Controversy on campus

It all started on Tuesday, December 2, 2014, when a small group of students organized a peaceful protest to show solidarity with the people of Ferguson, Missouri, after the grand jury failed to indict police officer Darren Wilson for the shooting death of Michael Brown.

My student journalists had known for a couple of days that the protest was planned; signs around campus alerted the entire community that the students would gather in the Rotunda of the Liberal Arts Center at 2:20 p.m. What they didn’t know would happen is that one student—who had just joined The Wood Word staff earlier in the semester, and who is not a journalism major—was planning to protest using the desecrated flag. Campus Safety almost immediately asked the student to remove the flag, and likely out of fear of punishment, the student complied.

But prior to the flag being removed, The Wood Word’s editor-in-chief, Autumn Granza, snapped photographs of the protest and flag and posted them to the newspaper’s Facebook page.

Of course, one of our own staffers becoming a newsmaker presented an added ethical challenge. People on our campus even insinuated that the student journalists had staged the protest in order to cover it. In an effort to be as transparent as possible, they released a statement explaining the conflict of interest, and the safeguards they were putting in place to ensure that the student had no role in the reporting, writing, editing, or publishing of stories about the protest.

But that wasn’t the only backlash. Almost immediately, the story became a viral sensation—at least in our local community. The Wood Word’s followers increased by an unimaginable magnitude—about 10,000 percent in five days. The Facebook post containing the image of the flag reached more than 27,000 people, and garnered more than 1,000 Likes, Comments, and Shares.

To put that into perspective, The Wood Word’s most-liked/commented/shared story in the same month was of Marywood’s Annual Christmas Tree Lighting, with 64 Likes, Comments, and Shares.

The comments on the flag photos, of which there were hundreds, ranged from disappointment to outright anger, with some including threats of violence.

- Kevin Blacketter Embarrassed to say I am an alumni of this University, please refrain from ever requesting a donation from me.

- Gabie Tornabene Disgusting what they did to our flag. Can’t believe I give my money to this Catholic institution. Even if the students took it upon themselves to do this, where was Marywood faculty to stop it. This represents our school as a whole and it’s embarrassing/disgusting to our reputation.

- Thomas Erickson Who in there [sic] right mind thought this was okay to post on social media. I really hope this goes viral.

- Matt Roman They need to be put down like the animals they are

- Mikey Falco expel them

The local media got ahold of the story, and that drew even more attention. Local journalists congratulated my student for breaking the story. But I learned later that just about the same time my students were getting pats on the backs from our local media, our administration was toying with the idea of asking us to simply make it all go away.

Administrators react

That’s when I got the phone call—the next morning at 9 a.m. I was practically waiting for it. I won’t lie; I was nervous.

The truth is, the phone call was pleasant, and the voice on the other end of the line was both rational and respectful. For that, I was grateful. It didn’t so much ask me to have the students remove the photo as much as it asked me whether I thought it would be appropriate for the administration to make such a request.

I said, Of course not.

I advised that censoring the student newspaper after they’d already censored a student protester was only going to dig them into a deeper 1A hole. Better to deal with the matter at hand with some thoughtful counter-speech.

That phone conversation was the last I heard about the controversy from the administration. They released their official statement, in which our university President, Sr. Anne Munley, I.H.M., Ph.D., said the following:

“As stated yesterday, Marywood University understands our students’ First Amendment rights to freedom of speech, peaceable assembly, and freedom of the press, but we abhor the desecration of the United States flag. Such an action is inconsistent with the mission of Marywood and our core values. As an institution of higher learning, we recognize that the circumstances of yesterday have created the opportunity for education and dialogue. Due to the nature of the events, disagreements are expected; it is our hope, however, that this will be a learning experience for our students and for all in the broader community who wish to engage in respectful dialogue.”

I’m not naïve. I know that having a “desecrated flag” on campus is going to create some discomfort and backlash, especially from the Student Veterans Alliance and the veterans in our local community—of which there are many.

In the past few years, Marywood, in its continuing effort to educate the underserved, has implemented programs to help returning veterans achieve their educational goals through transition programs and support centers. The efforts—that had been covered by The Wood Word—are admirable and worth celebrating.

Likely in fear of alienating that faction of the community, as well as trying to contain the outrage of alums and donors, Marywood was working overtime trying to minimize the harm that the student protest has caused. Marywood, like most other small, private universities, is facing challenges as enrollments decline nationwide.

I was working overtime, too. At first, it was in an effort to educate my student reporters as they scrambled to cover the protest and its aftermath. That week was full of long days, longer nights, and restless sleep as I worried whether I was doing the right things as I counseled the students on their reporting. Though classes ended that week, the controversy would not.

To read more about The Wood Word’s coverage of the campus protest, check out the following links:

- EDITOR’S NOTE: Our coverage of the Ferguson protest

- NEWS: Campus protest stirs controversy, leads to learning moments

- EDITORIAL: Our Opinion: Looking back to move forward

Troubling questions

In the days that followed, I found myself educating my colleagues about the role of the student press, but also about my dual role as professor and student media adviser. Perhaps most shocking were the questions I encountered related to the First Amendment from my colleagues.

Is writing on a flag illegal?

A quick Google search will show that no, writing on a flag is not illegal. It’s a form of protected speech under the First Amendment.

But, did The Wood Word really need to post that photo? It wasn’t really news. To whom would that have been important?

This protest is the biggest news to hit our campus in months. Knowing what our students are doing and thinking about, I would hope, is of utmost importance to all of us in the Marywood community. (Should I go through my lesson on News Values next, I wondered?)

Shouldn’t the students have gotten approval before posting those photos to The Wood Word’s Facebook page?

That would constitute prior review. While I often do work with students as they draft stories to ensure that they’re learning through the process, I never tell them to run or not run a story that’s been well-reported; that’s their call and they know it because I’ve taken great pains to teach them as much. They need the freedom to do real journalism in order to improve their skills and to eventually move on from Marywood and get a job.

Weren’t you worried about how bad this was going to look for the university? You probably should have thought about that.

I’m a professor here, too. I know the realities of our marketplace, the importance of enrollment, and the damage negative publicity could cause. But, I can’t control what people think about this event any more than I can control whether it snows on the day I’m scheduled to give two final exams. And my job is to educate our student journalists, not to be the University’s crisis manager. I will not teach my students that censorship is OK when it’s in the name of crisis management.

Did I really just hear you say that you’re proud of the students for doing something that’s hurting the university?

Yes. Of course I’m not happy that the University is getting hit with the truly undeserved community backlash. But, I’m proud that my student journalists are taking initiative to report breaking news on our campus. I’m proud of the careful and ethical way they handled the coverage in the event’s aftermath. I’m proud of their editorial leadership in our community. When no one else was speaking up publicly about these events, my students had the courage to do so.

Weren’t you nervous when the VP called you?

A little. But, I won’t compromise my own personal ethics. I won’t censor my students or compromise my own academic and journalistic integrity. I was prepared for whatever heat was about to come my way. But advisers shouldn’t have to fear for their jobs for doing their jobs.

Even more troubling questions

Equally troubling were some of the questions that non-journalism students asked me, like:

- Would you consider asking The Wood Word not to write a story about this?

- Why was my name used in the article? Hours after I did the interview, I asked the reporter not to use my name.

- Maybe your reporters could carry waivers that students could sign when they’re interviewed so they’ll understand how journalism works?

The most troubling questions

They came from my student journalists:

Are we going to get in trouble?

I hope not.

Can this get you in trouble?

I hope not.

Thanks for being a role model and standing up for what’s right, even when it’s hard.

Where do we go from here?

These questions and this event helped me to realize how much work needs to be done to educate not only the people on my campus, but the citizenry in general, about media literacy, the First Amendment, and the role of the press in democracy. Nothing could be more important in society today.

But it’s clear from this story, as well as from the ones out of Muscatine Community College and North Michigan University, that university administrators need the most education about the First Amendment. Their power posture when it comes to negative press is jeopardizing journalism education.

It’s imperative that organizations like College Media Association, the Society for Professional Journalists, the Society for Collegiate Journalists, and the Student Press Law Center take up this cause in a tangible way. Issuing statements decrying administrators’ behavior, as the aforementioned organizations have done in the North Michigan case, is a step in the right direction. But we need to go further.

We need to provide media advisers with tools for educating their campuses about their role and for fostering environments that are truly supportive of the First Amendment and the student press. Those tools might include:

- Training to help advisers educate campus administrators about their role and the role of the student press.

- Training for student journalists about how to use their media to educate their campuses about the First Amendment.

- Information kits for campus administrators that include materials about the First Amendment, the value of a free student press, and perhaps crisis management alternatives to censoring the student press.

- Media literacy webinars that student media organizations can stream publicly on campus to help educate students, professors, staff and administrators about the role on the student press and how they can engage with student journalists.

- Creative social media campaigns that can promote free campus presses and support for student journalists.

Some good existing resources include:

- The First Amendment Center

- The Student Press Law Center

- American Civil Liberties Union

- Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (F.I.R.E.)

- College Media Association’s Adviser Advocacy Program

- Society for Professional Journalists’ Campus Media Statement Program

As media advisers, we’re constantly educating our student journalists about how to do good journalism. We need to remember that it’s equally important (albeit sometimes frustrating) that we educate the members of our campus community about our role, our student journalists’ roles, and their role in engaging with campus and other presses. Nothing is more important to the future of journalism education and to our democracy.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Lindsey Wotanis, Ph.D., is an associate professor of communication arts and director of the broadcast journalism program at Marywood University, a private Catholic institution in Scranton, Pa. She serves as co-adviser to the student-run newspaper, The Wood Word, which publishes six print editions each academic year and online frequently. Since she became a co-adviser in 2010, the newspaper staff has won 23 national awards. She currently serves as Vice President for Communication for the Society for Collegiate Journalists (SCJ), the nation’s oldest organization designed solely to serve college media leaders. She was named SCJ’s Outstanding New Adviser in 2013.