Campus journalism that serves a bilingual audience heads into third year

By Marcy Burstiner

Humboldt State University

When I came up with the idea for El Leñador, a Spanish-English student newspaper, at Humboldt State University in Arcata, California, I hadn’t spoken Spanish since high school.

Moreover, I taught on a campus with one of the least diverse student populations in the California State University System, and my idea came at a time when The Lumberjack, the student-run weekly newspaper I advised, was struggling for advertising revenue. And, the university was looking for programs to eliminate to make up for state budget cuts.

But there were reasons to proceed with this new publication. Among them: The university had been named a Hispanic-Serving Institution, a designation that would make it eligible for new funds, and the Latino student population had doubled as a percentage of the overall student population between 2009 and 2013. At 28 percent, it was now about three times the percentage found in the rest of the county. Humboldt State’s enrollment is about 8,485.

I hoped that for a newspaper for and about the Latino student population, the administration would help me find the money I needed. I teamed up with Dr. Rosamel Benavides-Garb, the chair of the World Languages and Cultures Department, who taught Spanish. We tapped into a fund our dean had for faculty-student research projects and secured small stipends for six students from our two majors to research models for bilingual newspapers.

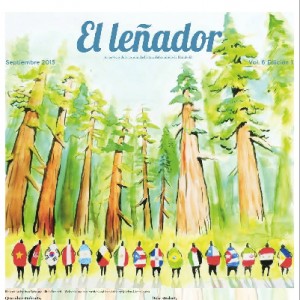

El Lenador, a monthly that averages six pages, is in its third year. Student Juan Carlos Salazar, a member of the initial research team who directed translation for the first two years, said the mission was daunting at first.

“I felt nervous,” Salazar said. “We were going to be the foundation of the project. I didn’t want it to fail. But I thought, ‘We are going to do this and be strong and continue to the future.’ My confidence grew and I knew I was going to be part of something great.”

El Leñador needed its own identity. So it would pay for its own pages and have its own equipment. Its staff would earn stipends comparable to those earned by students on the weekly. We secured $3,700 from an alumni fund for student projects and $8,000 from the Office of Diversity and Inclusion.This money would pay for a pilot issue, 10 more the next year, a camera, computer and software licenses.

A fund for Instructionally-Related Activities increased funding by $5,000 with the understanding that the money would be used to incubate the new bilingual monthly.

Half the staff came from outside the journalism major and took no journalism courses. Many were actively involved in Latino organizations; they had conflicts of interest they couldn’t and didn’t want to avoid.

As a result, El Leñador has been less objective and more activist than The Lumberjack. This became clear in the final issue of its first year when El Leñador assigned student Adrian Barbuzza to cover a forum held in response to protests by Latino students over a painting called “Super Taco,” which the university had bought and hung in the cafeteria.

Painted by a white student, Super Taco portrayed Latino workers in the kitchen of a fast food restaurant. The message many Latino students got from the painting, in that location. was the opposite of what the university had intended. The forum was so packed and so polarized — Latino students and staff facing off against defensive art majors — that it had to be moved to a much larger room.

“ I was assigned the story,” Barbuzza said. “But I was personally involved in getting the forum going. I had to be able to report effectively and not let my passion get in the way of my reporting.”

But it was in the Super Taco coverage that we realized how much El Leñador was needed. It reported the story in a way The Lumberjack could not.

By the end of the second year, the confidence level was so high, that the editor decided that the paper could have a completely different structure than the Lumberjack. He thought it didn’t need a centralized leadership. No top editor. In part, he worried that there was no one experienced enough to succeed him.

But without a central leadership structure, I told him, there was a good chance the paper would fall apart – arguments would arise and the staff would split into factions that might not be able to work together effectively. The top priority for the first few years needed to be ensuring the publication’s continuity. He needed to appoint a leader, or the staff needed to choose one, and then empower that person.

He did.

We worked on an independent distribution system. The heart of the Latino community was around the town of Fortuna, much further south that the three towns where we distributed The Lumberjack. We arranged for Salazar to take the papers there on a regular basis. People grabbed them up.

“The audience wanted more articles, “Salazar said. “The radio station in Spanish would recognize certain articles and tag us on Facebook. We began seeing El Leñador as a voice and outlet for the wider Latino community.”

El Leñador started publishing independently a year sooner than we had anticipated, because of a mistake. Something went wrong with the fall 2014 issue: The headline ended up so badly misprinted we made the decision to reprint the El Leñador pages separately and discovered that it cost less to print El Leñador separately than to add the extra pages into the regular printing of The Lumberjack.

Staffs of The Lumberjack and El Lenador share a newsroom. However, they try to coordinate different production nights, as both staffs have outgrown the small newsroom. While students are encouraged to join both newspaper staffs and the two publications are encouraged to work together as much as possible, the publications seem to be competitive by nature.

Growing El Leñador remains a challenge. We don’t want it to siphon Latino students away from The Lumberjack and end up with a rivalry based on ethnicity. And while we expect El Leñador to tap into potential ad dollars from Latino businesses looking to reach a Latino consumer market, the university has presented some obstacles preventing the paper from hiring its own ad representative.

And after two years in operation, El Leñador needs its own faculty adviser, one with journalism experience who speaks and read Spanish fluently and, if at all possible, comes from a Latino background. Finding that person on an adjunct basis in a rural county five hours from San Francisco is difficult—but not impossible.

What we have found on El Leñador is that if we really want to make it happen, we will figure out the way to do so.

Marcy Burstiner is chair of the Department of Journalism and Mass Communication at Humboldt State University. She advises two student newspapers: The Lumberjack and El Leñador. She is the author of the textbook Investigative Reporting: From premise to publication, which was published by Holcomb Hathaway in 2009. Prior to joining the HSU faculty she was assistant managing editor for The Deal financial magazine and website and senior reporter for thestreet.com. She is the co-founder and chair of the Humboldt Center for Constitutional Rights. She has a masters in science from the Columbia University Journalism School.